Above video (link): source here.

The use of nuclear weapons against civilians in the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki seventy years ago has immediate and ongoing importance to every single human being to this day.

If there is any justification for the use of force, for the development of martial prowess, the justification lies in the possibility that martial skill can be used to prevent the murder of innocents.

The development and use of weapons for the express purpose of murdering noncombatants is a hideous perversion of that.

The principle of non-murder should be the most uncontroversial and straightforward principle in the world. There really is no argument that can justify murder, although there are those who will somehow try.

Robert Oppenheimer was a gifted physicist who was recruited by the US government to help develop atomic weapons, and whose abilities appear to have played a major role in the development of the atomic weapons that were used on the people of Hiroshima and Nagasaki with such devastating and murderous effect.

Many of the articles that have been published at this seventieth anniversary of the use of those bombs on Hiroshima (where a uranium-based bomb was dropped on August 06, 1945) and Nagasaki (where a plutonium-based bomb was dropped on August 09, 1945) cite Oppenheimer's statement that when his device was successfully tested in the desert of New Mexico in July of 1945, he and everyone present knew that this successful test of this weapon would change the world forever.

He later said that he could not help but think of a line from the Bhagavad Gita: "I am become death, the destroyer of worlds." Oppenheimer made this statement in 1965 during a televised interview. The use of this line by a figure of Oppenheimer's stature, on national television, has indelibly linked it with the development -- and use -- of this weapon.

This is a line spoken by Lord Krishna in the eleventh section or chapter of the Gita, when Krishna reveals his infinite form to Arjuna. It is specifically found in the thirty-second sloka (shloka), which can be seen in a variety of locations on the web, in Sanskrit characters, in Sanskrit rendered in the modern English alphabet, and in various translations in to English.

Here is one such site, which includes the Sanskrit characters as well as a transliteration with literal phrase-by-phrase translation (and a vocal recording of the spoken Sanskrit), and here is another which includes only the transliteration of Sanskrit into English alphabetical letters along with a slightly different translation into English.

In the first translation, the words of this important verse are rendered this way:

Lord Krishna, the possessor of all opulences, said: I am terrible time, the destroyer of all beings in all worlds; of those heroic soldiers presently situated in the opposing army, even without you none will be spared.

In the second, the passage is translated thusly:

The Supreme Personality of Godhead said: Time I am, the great destroyer of the worlds, and I have come here to destroy all people. With the exception of you [the Pandavas], all the soldiers here on both sides will be slain.

Here is a different translation from another site:

Said the Lord Supreme, "I am Time, verily the great destroyer of the Worlds engaged now in the destruction of people. Even without you, all the warriors on either side are going to be destroyed."

Clearly, many translators see the original word as indicating a personification of all-devouring Time, rather than "Death" as Oppenheimer apparently did. Perhaps Oppenheimer was quoting from a different translation (unless Oppenheimer, or someone who gave him the quotation, deliberately altered the translation of the sloka in order to make it convey a certain impression to the listener that demanded the use of "death" rather than "time").

Whatever Robert Oppenheimer intended to convey with his use of this particular line of the Bhagavad Gita in this instance, I believe the entire message of the Bhagavad Gita -- as well as the very specific message of this particular sloka -- can be seen as urging every single one of us to stand up for what is right, against the murder of innocents.

It is a message that is absolutely opposed to passive resignation in the face of deliberate, scheming evil: in fact, the second half of the verse (which Oppenheimer did not quote in the televised interview) contains a promise from Lord Krishna that, whether or not Arjuna decides to stand up against the evil forces personified in the ancient epic in the form of the Karauva army, the outcome is already determined and Krishna has promised victory. The only question is whether or not Arjuna will participate as an instrument of the divine will, or whether Arjuna will decide to "sit this one out."

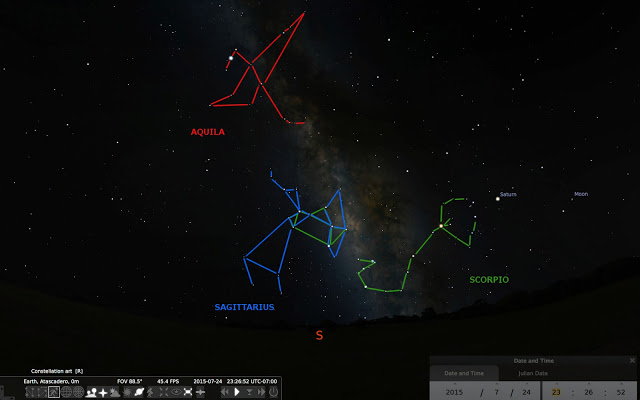

Note that in saying this, I am absolutely not trying to literalize the Bhagavad Gita: I am not saying that it is about a war that took place in ancient times, or that it is (by extension) directly applicable to any modern war, in which one country or combatant army can be identified as one side or the other. I have already written extensively on the evidence I find for concluding that the Bhagavad Gita is a celestial allegory that has to do with the struggle of the soul (that is to say, each and every human soul) in this incarnate existence: see this previous post and the video embedded in that post.

The mighty battle into which Arjuna is preparing to descend is the spiritual battlefield of this incarnate existence -- and the foes which he is facing include lust, anger and greed, which Krishna identifies elsewhere in the Gita (such as in the twenty-first sloka of section 16) as the three gates to Naraka, the underworld. Krishna's message to Arjuna prior to descending into this allegorical "battlefield" (which, as I have shown based upon celestial evidence and based upon the invocation of the goddess Durga immediately prior to the Bhagavad Gita is almost certainly the "battlefield" of this incarnate life) is that Arjuna should devote himself to right action -- action which is specifically described as not harming others -- that he should do this right action without concern for or attachment to the outcome, and that he should do what is right because it is right, and not out of any hope for either material or spiritual reward.

I have also argued that the Bhagavad Gita (and other ancient texts) are trying to teach us that in order to achieve the goal of right action without attachment to results that Krishna is counseling Arjuna to pursue, we must find the inner connection to the infinite which we all already have. When Krishna reveals his infinite form to Arjuna in the eleventh section (where the quotation in question is found), he is, I believe, imparting this very teaching. For more on that subject, see this previous post.

If the Gita is not literal but rather metaphorical, then it cannot be woodenly applied in a literalistic fashion as if the "good guys" in the ancient myth correspond to "my country" and the "bad guys" in the ancient myth correspond to "the other guys" (although this is in fact the way that literalists sometimes try to apply ancient scriptures, in order to condone a war they are promoting). Instead, I believe that Krishna's message is that we are to stand up against violent and destructive and callous forces within ourselves, as well as against violent actions by others, such as the violent and invasive behavior which is exhibited by the Karauvas who oppose Arjuna and his brothers in the metaphorical Battle of Kurukshetra in the ancient text.

Krishna here promises that these destructive forces will in fact be defeated and that victory is already assured (as the goddess Durga also promised when she appeared to Arjuna, in the chapters immediately preceding the Bhagavad Gita). He says that this ultimate victory will happen "with or without" Arjuna's participation -- but that Arjuna is actually designed for that struggle against evil and that it is actually his duty to participate in the metaphysical battle.

Again, I believe it can be conclusively demonstrated that this scripture is not directed to some ancient semi-divine warrior named Arjuna who is about to participate in an ancient battle on the plain of Kurukshetra: everything Krishna is saying is directed to each and every human soul, which comes down into this incarnation to participate in the struggle. The eventual victory is already assured, as both Durga and Krishna assure Arjuna: the question is whether or not we are going to participate, and the degree to which we will do so.

The Bhagavad Gita specifically states, in its eighteenth and final section or chapter, that taking no action at all is not really possible for any incarnate being. The only question is whether or not that action will be right action. Here is the relevant passage from the eighteenth chapter beginning at the eleventh sloka as found on this website (and you can also compare this website, which gives the original Sanskrit characters as well as a literal phrase-by-phrase translation, and this website which contains the 1885 translation by Edwin Arnold which, although poetic and somewhat flowery, actually has much to commend it, if examined carefully):

11 It is indeed impossible for an embodied being to give up all activities. But he who renounces the fruits of action is called one who has truly renounced [literally "Tyaga"].

12 For one who is not renounced, the threefold fruits of action -- desirable, undesirable and mixed -- accrue after death. But those who are in the renounced order of life have no such result to suffer or enjoy.

13 O mighty-armed Arjuna, according to the Vedanta there are five causes for the accomplishment of all action. Now learn of these from me.

14 The place of action, the performer, the various senses, the many kinds of endeavor, and ultimately the Supersoul -- these are the five factors of action. [Another version, from the second website linked above, reads: "The body, also the ego, the different separate perceptual senses, the various yet separated vital forces, and the fifth being the Ultimate Consciousness as the indwelling monitor."]

[. . .]

20 That knowledge by which one undivided spiritual nature is seen in all living entities, though they are divided into innumerable forms, you should understand to be in the mode of goodness.

[. . .]

23 That action which is regulated and which is performed without attachment, without love or hatred, and without desire for fruitive results is said to be in the mode of goodness.

24 But action performed with great effort by one seeking to gratify his desires, and enacted from a sense of false ego, is called action in the mode of passion.

25 That action performed in illusion, in disregard of scriptural injunctions, and without concern for future bondage or for violence or distress caused to others is said to be in the mode of ignorance.

26 One who performs his duty without association with the modes of material nature, without false ego, with great determination and enthusiasm, and without wavering in success or failure is said to be a worker in the mode of goodness.

Note that action performed without concern for violence or distress caused to others is condemned: it is not right action. Krishna tells Arjuna to do what is right without attachment to results -- he condemns doing what is causes violence or distress to others (and specifically condemns causing violence or distress to others without concern for those results).

The Bhagavad Gita elsewhere (most strongly perhaps in the sixteenth chapter) reiterates its condemnation for those who declare that there is no law in this life, no divine rule, and who give themselves up to evil deeds, and the ruination of others. Krishna vividly describes those following such a path:

Slaves to their passion and their wrath, they buy

Wealth with base deeds, to glut hot appetites;

"Thus much today," they say, "we gained! Thereby

Such and such wish of heart shall have its fill;

And this is ours! And the other shall be ours!

Today we slew a foe, and we will slay

Our other enemy tomorrow! Look!

Are we not lords? Make we not goodly cheer?

Is not our fortune famous, brave and great?

Rich we are, proudly born! What other men

Live like to us? Kill, then, for sacrifice!

Cast largesse, and be merry!" So they speak

Darkened by ignorance; and so they fall --

To bring this discussion from the Bhagavad Gita back to the horrendous act of creating atomic weapons to be used against the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki to kill hundreds of thousands of noncombatants including women, children, teenagers, and elderly people (and the building of other, even more powerful nuclear weapons for the express purpose of threatening their use against other cities full of noncombatants also including women, children, teenaged and elderly people), it should be plain from Krishna's words that such actions are murderous and would be specifically condemned. The passage above from the Gita, in fact, should sound eerily disturbing in light of the way that the Bhagavad Gita was specifically evoked by Robert Oppenheimer in that 1965 televised interview about the dropping of the atomic bombs by the United States.

In fact, contrary to what has generally been taught as inviolable dogma in the United States since 1945, the act of dropping those bombs was widely condemned as barbaric and completely unnecessary by military leaders in many top positions in the US armed forces at the time!

This website, linked in a previous post last year at this same time, contains quotation after quotation from military leaders including General Douglas MacArthur, Admiral Chester Nimitz, Admiral William D. Leahy, Admiral William F. Halsey, Undersecretary of the Navy Ralph Bard, and many others who objected to its use and who went on record saying that the decision to drop the bomb had nothing to do with hastening the surrender of Japan but rather had something to do with other motives.

However Robert Oppenheimer meant that famous Bhagavad Gita quotation, which now links (in many people's minds) the widely-beloved scriptures of the Bhagavad Gita to the decision to develop and ultimately use atomic weapons against noncombatant civilians, it should be quite clear that the Bhagavad Gita itself actually enjoins us to stand up against such violence -- that in fact it argues that our very purpose here in this incarnate life, this Battle of Kurukshetra, is to stand up for the right regardless of the outcome and without attachment to the outcome, and without concern for whether or not we seem to be prevailing at the moment in our stand against such violence.

In fact, the wider context of the ancient Sanskrit epic of the Mahabharata, which contains the Bhagavad Gita, reveals the cause of the disastrous Battle of Kurukshetra to be the passivity of the blind king Dhritarastra to stand up against the greedy, violent, and fraudulent schemes of his son Dhuryodhana (assisted by Dhritarastra's wily brother-in-law, Dhuryodhana's uncle, Sakuni, who is a great dice-player and one who by his own admission uses deceit to win at dice-gambling, and who arranges a scheme to defraud the Pandauvas of all their possessions in a great dice match, because of Dhuryodhana's overwhelming greed and because of Sakuni and Dhuryodhana's violent hatred of the Pandauvas).

For more on Dhritarastra's blindness, see this previous post, and for more on his disastrous accommodation of the evil schemes of the members of his own household, read this chapter from Book II of the Mahabharata (section 48).

The lessons for us should be quite plain. It is now seventy years since the team of scientists led by Oppenheimer used their talents to create a weapon that was then used to murder hundreds of thousands of noncombatants.

Some military leaders stood up against the use of this weapon at the time, to one degree or another, although none to the degree that would actually stop the use of this weapon in 1945 to incinerate and poison hundreds of thousands of noncombatants (most of them women, children, teenagers, and the elderly) in two cities in Japan (which was already sending out signals that it wanted to sue for peace), and none to the degree that would lead the public to demand an end to a policy of building such weapons with the express purpose of pointing them at other cities full of noncombatants for the next seventy years (right up to the present day).

All of that generation of scientists and leaders have now left that incarnation, but we who are currently living still face the same questions that they faced. Do we condemn the violent schemes of the Sakunis and Dhuyodhanas in our own household? Or do we accommodate and enable it, as Dhritarastra did?

Are we using our talents to create tools and technologies that can be used by those who have no concern for violence or distress caused to others, and who sound like the "slaves to passion and wrath" described by Krishna in the sixteenth section of the Gita, saying to themselves "Are we not lords?"

And if we create technologies that we see could have disastrous or even apocalyptic consequences, do we stand up clearly against their misuse, even if we don't know if anyone else agrees with us, even if we don't know what the outcome will eventually be?

These were obviously important questions for those living seventy years ago, but they are just as important for those living today.

Ultimately, standing up against murder should be completely uncontroversial. It is really impossible to argue for it.

The use of the quotation from the Bhagavad Gita in conjunction with the creation of the first atomic weapons, and with the use of those atomic weapons to murder hundreds of thousands of men and women and children, should cause everyone who hears that quotation to examine what the Gita says about doing what is right in this life, standing up against violence, struggling against the "forces of Dhuryodhana" (so to speak).

And, when we hear that particular quotation from the eleventh chapter of the Gita -- the chapter in which Lord Krishna reveals his Supreme Infinite form, which is beyond all definition and boundary -- we should consider carefully what this teaches us. It teaches us that we each come down into this struggle, this battlefield of incarnation, with a connection to the infinite (as Krishna states quite plainly many times, including some of the passages quoted above). And it also teaches us that the outcome of the battle is in a sense already determined, and that the "forces of Dhuryodhana" are already defeated (as Krishna tells Arjuna) and that Arjuna ultimately cannot lose (as Durga tells Arjuna just prior to the Bhagavad Gita).

I believe that the policy of using nuclear weapons (or any weapons for that matter) to murder noncombatants as an express policy of war or "peace" is absolutely criminal. The historical record shows that many of the military leaders of the US from previous generations (those who were born and received their education prior to World War I, such as those cited above and in this catalog) would agree.

I believe it is also safe to say that the Bhagavad Gita, which is often cited on the anniversaries of the dropping of these hideous weapons on the noncombatant civilians in Hiroshima and Nagasaki (as if perhaps Krishna would somehow condone such wanton murder), would also condemn such killing of women and children and teenagers and aged people.

Perhaps this closer examination of the Bhagavad Gita will motivate us to read through its ancient wisdom more frequently, and with an eye towards its application in our daily lives, even in this most modern era in which we find ourselves living.

And perhaps the admonishments and encouragement offered by Krishna to Arjuna will spur us to stand up for what is right, against murder and other forms of violence to others, even if we are not sure of the eventual outcome (though Krishna himself apparently is!)

image: Wikimedia commons (link).