"Whew! You sure gotta climb a lot of steps to get to the Capitol Building here in Washington.

Well I wonder who that sad little scrap of paper is?"

And with those words began one of my childhood favorite Schoolhouse Rock videos, which used to be on television back in the early 1970s when I wasn't really old enough to have any idea what exactly they were all about, or why they would sometimes show up in between episodes of Superfriends, Speed Racer, or Sigmund and the Sea Monsters.

In I'm just a bill," we witness the progress by which "that sad little scrap of paper" receives a fancy seal and a president's signature and becomes a law ("He signed ya, Bill: Now you're a Law!").

Although the video does an admirable job depicting some of the checks and balances contained in the US Constitution, through which the members of both houses of the legislature must agree to send the bill forward to the executive branch for final approval before any proposed bill is signed into law, it does tend to convey the impression that any "good idea" can be transformed into "a Law" through the magical process of being debated by important-looking men in impressive-looking buildings with lots of steps and Greek columns, on top of high hills (and filled with long rows of impassive US Marines in dress blue uniforms, and statues of distinguished statesmen from previous generations), signed by the president using a fountain pen, and affixed with a shiny-looking seal with a ribbon.

Nineteenth-century abolitionist, legal scholar and philosopher Lysander Spooner (1808 - 1887) would vehemently disagree that something becomes "a law" just because it goes through the above process and receives a president's signature and a fancy stamp. In fact, he published a treatise in 1850 entitled A Defence for Fugitive Slaves against the Acts of Congress of February 12, 1793 and September 18, 1850, in which he argued that an illegal law is no law at all, and confers no obligation on anyone to obey it, nor any authority to anyone desiring to enforce it.

He begins his treatise with the complete copy of each of the two acts in question, both of which were considered "law" in 1850, compelling men or women who knew of a "fugitive slave" to help catch that "fugitive slave" or face penalties including fines and imprisonment (the term "slave" is put in quotation marks here because Spooner argues that no person can ever own another person, and that there actually is no such thing as a legal slave or the legal condition of slavery, all so-called "laws" which make one person the property of another being illegal and criminal).

Those two so-called laws (the Fugitive Slave Act of 1793 and the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850) were both signed by the presidents of their day, George Washington in the first instance and Millard Fillmore in the second (they also bear the signatures of the respective Speakers of the House and Presidents of the Senate). But these signatures do not make them true laws, according to Spooner's arguments. Spooner demonstrates that holding anyone else as property is a crime, and that putting something on paper, stamping it with fancy seals, embellishing it with fancy legal language, and endorsing it with the signatures of people bearing impressive titles does not make it into law: it's still just a "sad little scrap of paper" in his eyes.

He even goes so far as to say that men and women have the right to resist illegal laws, in what is undoubtedly among the most important sections of his argument, found on pages 27 and 28. There, he powerfully dismantles the counter-arguments that he anticipates from those who would argue that once something is "a law," it must be obeyed until it is repealed.

If it were really true that an illegal or unconstitutional law must be obeyed until repealed, he reasons, then "there would therefore be no difference at all between a constitutional and an unconstitutional law, in respect to their binding force; and that would be equivalent to abolishing the constitution, and giving to the government unlimited power" (28).

Those who would disagree with Lysander Spooner on this point are invited to participate in a mental experiment, in which they imagine that the president has signed a law saying that if you in any way hinder the search for an escaped slave, or in any way assist a person who has been designated a "slave" and who has run away and is hiding from the authorities, then you yourself are a criminal and can be subject to enormous fines and imprisonment. Note that this is not just a hypothetical scenario: the first and the thirteenth presidents of the United States each signed such a proposition into "law."

Today, nobody reading this blog would likely argue that they would feel a moral duty to obey such a "law," or that they would have to actually support it until such time as they could eventually get it repealed through the same arduous process depicted in the Schoolhouse Rock video shown above.

Nearly every man or woman would agree with Spooner that the institution of slavery and "laws" enforcing one person's ability to "own" another are not laws but rather outrageous crimes, and would reject the notion that writing such a "law" down on a piece of paper, stamping it with a pretty seal and adding some flowery signatures suddenly turns it into something that must be willingly and voluntarily obeyed until it can be debated and eventually repealed.

Writing something on a piece of paper does not make it a law.

But, if this is true, then what does make something a law? Lysander Spooner argued that the actions of men and women cannot actually make anything a law, but that there is already an immutable or unchangeable universal law which he called "Natural Law" or the "Science of Justice." He believed that human society should only enforce natural law, and not dream up additional or "artificial" laws, and that trying to add to or subtract from the natural law is as foolish as trying to add to or subtract from other natural laws, such as the law of gravity.

He argued that men and women could voluntarily band together to help ensure compliance with this natural law among their group, but that they could not compel others to join that voluntary association. Even within such a voluntary association, he believed that people or groups could only rightly compel compliance with the natural law, which was generally extremely simple and basically entailed the command to "live honestly, hurt no one, and give everyone his or her due."

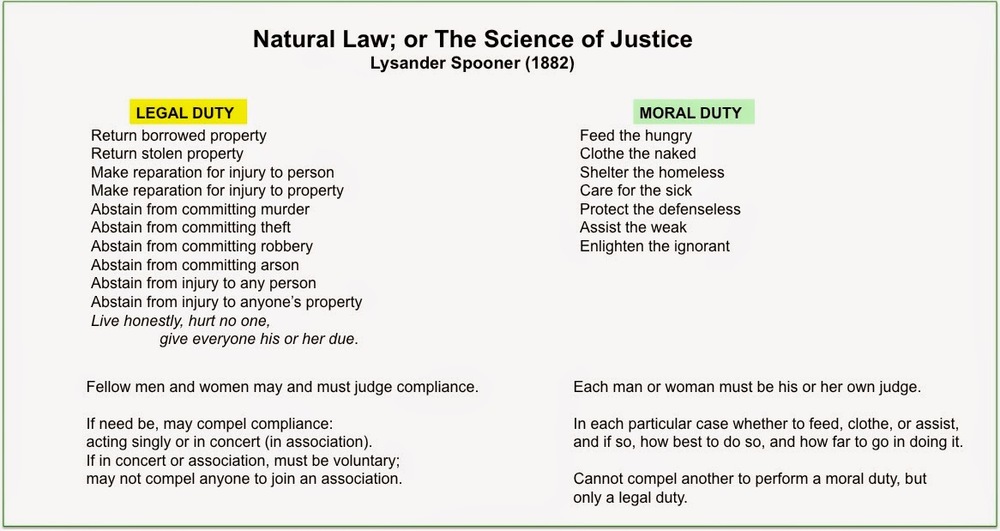

In an 1882 publication entitled Natural Law; or The Science of Justice, Spooner set out to explain the concept of natural law. In it, he made a distinction between those things that everyone has a legal duty to either do or to refrain from doing, and which others can and must compel in others, and those things which everyone has a moral duty to do but which must be left up to each person's own judgment and which no one has the right or duty to compel.

Below is a table based upon Spooner's 1882 text, generally following the order and wording of his argument:

The left column (labeled "Legal Duty" and highlighted in yellow), in Spooner's view, constitutes those things which are part of the natural law, and can actually be the only things which anyone can rightfully use force to uphold. He says that everyone has a duty to refrain from injuring others, and that force may and must be used when someone sees someone else in the act of injuring someone else. Spooner further argues in that 1882 text that nearly everyone understands these natural law prohibitions and duties before they are even old enough to know that "three and three are six, or five and five ten" (9).

The right column (labeled "Moral Duty" and highlighted in green), in Spooner's view, constitutes those things which we do have a moral duty to perform, but which no one else can compel us to do: we must judge the extent to which we are able to do those things, and how we wish to best accomplish them when we do decide to do them.

Thus, in Spooner's view, any so-called law that goes beyond the legal duties in the left column (or, worse yet, directly contradicts and violates those legal duties, as did the Fugitive Slave Acts) is actually no law at all and it can and must be disobeyed as illegal and criminal, regardless of whether it was written down on paper using legal-sounding language and passed by men and women in fancy buildings and stamped with fancy stamps and inscribed with fancy signatures.

At this point, the reader may be thinking that all of this is very nice, but what on earth does it have to do with the general subject matter covered in this blog?

The answer is: everything.

Because, as insightful thinkers such as Mark Passio have articulated, violations of natural law are so contrary to our innate understanding of right and wrong (remember that Spooner says we know it before we even know that 3 + 3 = 6) that artificial laws which violate natural law must always be dressed up with various symbols and word-formulas designed to convey legitimacy, and reinforced by systems of mind control by which men and women who should know that those violations are immoral can somehow be made to believe that those violations of natural law are instead right and good and deserving of support.

Institutionalized violations of natural law are nearly always accompanied by powerful forms of illusion, or the creation of "false realities" that enable those violations to appear legitimate, and to get people to go along with them.

Therefore, seeing through these false realities is of absolutely primary importance. This blog primarily examines false realities which can be seen operating all around us, including in the realm of conventional history as taught in all the institutions of academia and reinforced by the organs of the conventional media (see for example "Piercing the fog of deception that hides the contours of history" and also the two short videos entitled "The importance of challenging false narratives").

These false realities or false narratives which cause people to accept gross violations of natural law are operating today with just as much force as they were operating in Spooner's day -- perhaps even more so.

False narratives assist in getting people to accept the premise that so-called "laws" permitting government surveillance of individual men and women at virtually any time and place are legitimate (see here and here). This is a violation of natural law in that it enables hidden enforcers and observers to treat individuals as criminals on the suspicion that they might do something to harm others, elevating some to the status of "prison guards" and demoting everyone else to the status of prisoners under constant suspicion and surveillance.

False narratives convince people to accept the idea that men and women can and should be locked up and denied their freedom for possessing certain plants or mushrooms known to induce a state of ecstasy. This is a violation of natural law in that it uses force to prohibit behavior that in no way harms the person or property of another or infringes on another's rights.

False narratives convince people to accept the idea that men and women representing the government and wearing military gear and driving military vehicles can point military weapons at people assembling in the streets to express themselves, or at people in their homes in a neighborhood where fugitives are supposedly hiding. These are clear violations of natural law in that such actions basically declare that force can be used against citizens whenever it is convenient for the government to say there is a need to do so, an idea which Spooner eloquently demolishes in pages 27 and 28 of his text against the Fugitive Slave Acts. In a passage labeled "Section IV" of his 1882 treatise on Natural Law, Spooner declares that the rights belonging to every human being by the unchangeable principle of justice "necessarily remain with him [or her] during life," and although these rights are "capable of being trampled upon" they are nevertheless "incapable of being blotted out, extinguished, annihilated, or separated from" each and every human being, and that there is no authority high enough to simply declare them null or void.

False narratives have even apparently convinced some people that it is somehow excusable to cover up evidence of the potentially harmful effects of vaccines on certain children in order to support "herd immunity."

All of the above examples, along with the many other violations of natural law currently taking place, are enabled and excused by a variety of false realities or false narratives, created and maintained in order to lend an air of legitimacy to these violations. So were many other horrendous violations of natural law which were enabled by false narratives and illusions throughout history, including the enslavement of Africans which Spooner argued against in the 1850s, to the destruction of Native American tribes in the western US after the end of the US Civil War and the seizure of their lands and their confinement to reservations or "agencies," to the seizure of the Hawaiian Islands and the Philippines in the years after that, and on and on right up to the present.

All of the above examples were enabled by lies, illusions, and false narratives or false realities. For more on breaking through illusions and false realities, and creating new realities, see for example this previous post entitled "Jon Rappoport's talk on the trickster-god and creating reality."

It is one of Lysander Spooner's singular contributions that he perceived and forcefully argued that a criminal "law" is no law at all, and that men and women have the right and the duty to treat it as such, and to inform others of their right to do the same.

Putting something on paper doesn't make it a "law" -- even if it has been adorned with all the necessary stamps and signatures. As Spooner alludes in the writings linked above, the US Constitution as originally designed, and especially the Bill of Rights as originally conceived, were designed to safeguard natural-law rights in many ways, and to the extent that Schoolhouse Rock taught those principles to a new generation in the 1970s, it can be commended. Perhaps Spooner's arguments about an illegal law being no law at all could not really be expected to be squeezed into the "I'm Just a Bill" song.

But Lysander Spooner's arguments deserve to be brought into the modern era, in much the same way that the creators of Schoolhouse Rock tried to speak to the younger generation of the 1970s using the language and imagery of the 1970s. Spooner's arguments on behalf of the individual's rights under natural law -- rights which could never be abridged by any authority -- and his arguments against the creation of arbitrary "laws" which everyone has to obey just because a legislature or a president gave them the title of a "law" deserve examination, consideration, and thoughtful debate today more than ever.

And the false narratives supporting so-called laws which supposedly authorize some people to use violence against others, or to threaten violence against others, or to take away the freedom of others when those others have not done anything to harm anyone else's persons or property, must be shown to be the form of mind control that they are. No individuals or groups can give themselves the right to violate natural law and in doing so to infringe on anyone else's rights, simply by writing something down on a "sad little scrap of paper."