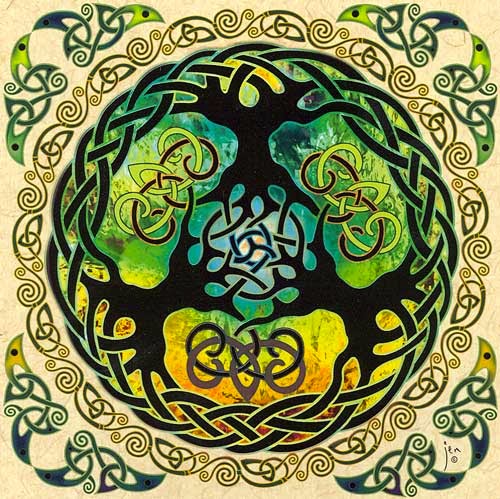

image: Wikimedia commons (link).

The previous post on "The sacrifice of Odin" presented abundant evidence that the important Norse god Odin is a shamanic figure, frequently depicted as undertaking journeys in search of hidden knowledge, and knowledge which specifically can only be obtained through shamanic methods.

The most central and most shamanic of all of these vision-quest journeys undertaken by Odin is undoubtedly his ascent to hang himself upon Yggdrasil, sacrificing in his own words "myself to myself," wounded with "the spear" which we can assume would likely mean deliberately and with his own spear Gungnir, and through a nine-night-long ordeal eventually obtaining a breakthrough into another reality in which he sees with non-ordinary vision the secret of the runes.

We saw that the power of the runes is far more than "just writing" (as if the power to write, which most of us take for granted, is not incredible enough in and of itself): the ability to see and know and use the runes implies the ability to create worlds through the power of words, sounds, language, speech, and mind. In a very real sense (as Shakespeare, George Orwell, and a host of other thoughtful writers have perceived) we are composed of our thoughts and thought-patterns and narratives, and those thoughts and thought-patterns and narratives are ultimately composed of words and of language, that is to say of symbols -- and we could say of runes.

Students of Old English will know that the very word "spell" which in modern English means a formula to alter reality was the Old English word spel that meant generally "word" or "message" (and hence the English word gospel is derived from the combination of the Old English words god pronounced "gode" and meaning "good" and spel meaning "word"). This fact reflects and illustrates the reality-altering power of words, language, and runes.

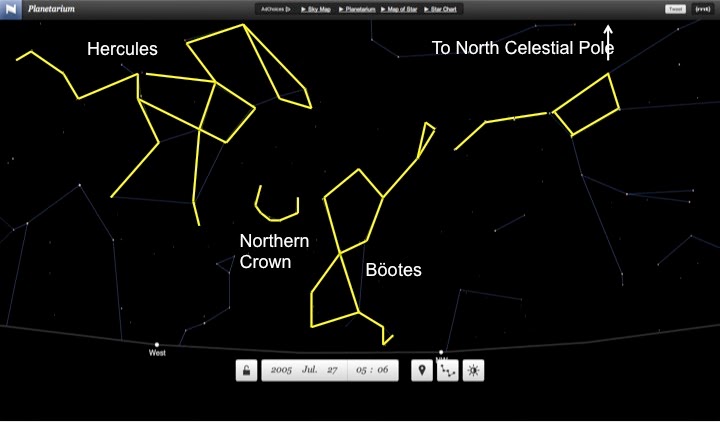

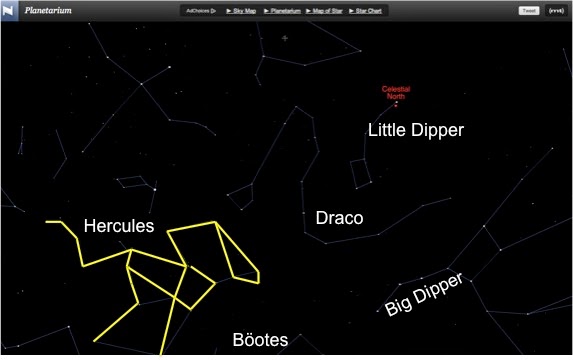

Interestingly enough, in light of the tremendous reality-altering power of words (and runes) is the fact that in order to obtain the knowledge of the runes, Odin had to undertake a journey that is clearly shamanic in its elements, including the ascent up a pole or tree: examples abound of the use of a pole or "tree" in the ritual shamanic journeys described in Mircea Eliade's compendium of shamanic observations from around the world entitled Shamanism: Archaic techniques of ecstasy (originally published in French in 1951). It is quite clear from the details of many of these shamanic poles that they represent the celestial pole, which is in fact the World-Tree, and thus they correspond directly to the "pole" upon which Odin had to ascend during his own ordeal to transcend ordinary reality and obtain the power of runic reality-creation and reality-manipulation.

Eliade offers numerous examples of shamanic rituals which involve, "as an essential rite, climbing a tree or some other more or less symbolic means of ascending to the sky" (123) including the "South American consecration, that of the machi, the Araucanian shamaness," who undergoes an initiation ceremony centered upon "the ritual climbing of a tree or rather of a tree trunk stripped of bark, called rewe. The rewe is also the particular symbol of the shamanic profession, and every machi keeps it in front of her hut indefinitely" (123). Eliade informs us that the rewe is always nine-feet tall in this particular culture, and that the multi-day ceremony involves drumming, drum circles, dancing, stripping naked, the sacrifice of lambs, falling into trance or the state of ecstasy, and the ritual cutting of the fingers and lips of both the shamaness candidate and the initiating shamaness, using a white quartz knife (123-124). Eliade then goes on to describe a shamanic initiation rite among the Pomo of North America involving "the climbing of a tree-pole from twenty to thirty feet long and six inches in diameter," and similar (and sometimes even more dangerous) symbolic ascents among shamanic cultures from the regions of Hungary, Iran, Australian aborigines, the Sarawak of Malaysia, and the Carib shamans of Dutch Guiana (125-131).

If the reader is not thoroughly convinced that this most central vision quest undertaken by Odin indicates his shamanic nature -- and is thus additional powerful evidence that all the ancient sacred mythologies are in fact shamanic in their core message -- there is the additional evidence that he is known for riding through the heavens upon his eight-legged horse, Sleipnir (shown in the upper section of the carved runestone above).

While other Norse gods and goddesses of course had horses too, Odin's was the horse most well-known, most unique, and most associated with his wild journeys through the heavens in the company of the wild band of the Valkyries (in this he resembles Dionysus, who was often accompanied by Maenads -- and whose rites in the hills and wilderness were described in terms indicating that they involved ecstasy). As the authors of Hamlet's Mill point out, the shaman's drum was described as the "horse" that serves to carry him or her into the state of ecstasy and to enable the shaman's soul to ascend to the sky (Hamlet's Mill, 122).

Odin's horse, Sleipnir, was notable for having eight legs -- four in the front and four in the back -- making him twice as fast as any other horse. Celestially, since Odin embodies the characteristics of the planet Mercury (who was also a transcendent god associated with breaking through barriers and with language, as explored in this important previous post), the fact that his swift steed Sleipnir had eight legs may be a mythological embodiment of the fact that Mercury is the swiftest of the planets (by virtue of its being so close to the sun). In fact, as you can easily confirm for yourself, the orbital period of Mercury is . . . 88 earth days! So, of course, Odin's steed would be expected to have eight legs -- what other number would have been appropriate?

But, if we see that Odin is clearly a shamanic figure, and that the shaman's horse is his or her drum, then the rhythmic drumming that would be produced by the hoofbeat of an eight-legged steed would be quite rapid, and quite apropos of the very rapid drumbeat used to produce a state of ecstasy in shamanic cultures around the world. So, the eight-legged nature of Odin's steed works to convey esoteric knowledge to us on many levels.

The previous post also demonstrated that the shamanic nature of Odin's sacrifice upon the Tree has direct parallels to the sacrifice of Christ upon the Cross. In The Undying Stars, I explore the ways in which the realization that all the myths of the world (including those found in the Old and New Testaments) unites the world's ancient wisdom, and leads to the possible conclusion that they were all at their very core conveying a message that is essentially and profoundly shamanic (that is, in fact, what I call shamanic-holographic).

This assertion is bolstered by the evidence that the celestial Tree which Odin must ascend (and which the shamans ascend in the ceremonies cited by Eliade) corresponds to the Djed-column of Osiris which must be "raised up" and to the Ankh or Cross of Life of ancient Egypt which has a horizontal component representing the "cast down" nature of our material existence (in which we must go about in an "animal" body), but which also has a vertical component representing our spiritual nature which comes down from above and which is immortal (a fact emphasized on the Ankh itself by the unending loop at the top of the cross), and which represents both the motion of our rise and return to the spiritual realms after each incarnation and also the motion of the raising of the inner spiritual component or fire which we can perform during this life as an essential part of our mission in this earthly existence.

We have also seen evidence that this "divine spark" in each individual man or woman is associated with the fire brought down from heaven by Prometheus in the ancient Greek mythos, and with the Thunderbolt or Vajra found in the ancient Vedic texts, and that the mission of recognizing this inner divine element and of raising it up is central to our overcoming our cast-down state.

And -- although "orthodox" (a word that means "straight-teaching" or by implication "right-teaching") and literalist Christianity would strongly object to such an assertion -- this mission of recognizing and the of raising up the divine inner spark can clearly be seen to be a possible interpretation of the message taught by Paul in some of his early letters urging his listeners to recognize the Christ within (Galatians 1:16, Colossians 1:27, 2 Corinthians 13:5) and to realize that they themselves undergo the process of being crucified and raised by virtue of this mystical identification with the Christ within (Galatians 2:20).

This connection advances the strong possibility that the patterns found in the ancient scriptures preserved in the Bible were actually the very same patterns found in the myth-system of ancient Egypt and the Djed-column and Ankh-Cross imagery associated with the Osiris, and the very same patterns found in the myth-system of the Norsemen and the World-Tree sacrifice associated with the shamanic questing of Odin.

It also supports the conclusion that -- like those other world-myths -- the symbology and esoteric message of the Bible scriptures is in fact deeply shamanic, and pointing towards the same individual ascent and breaking free of the bonds of the material body and the material world undertaken by shamans in the rituals recorded by Eliade and other researchers in the early twentieth century and in the centuries immediately preceding.

Powerful evidence, perhaps even conclusive evidence, to support this conclusion -- the conclusion that the imagery employed by Paul and the other early pre-literalist teachers was actually composed of exquisite metaphors designed to teach a message closely aligned with the message embodied in the Osirian imagery of "the Djed-column cast down" and "the Djed-column raised up," the same message found in the sacrifice of Odin and the Thunderbolt of Indra (the Vajra) and in the ascent to the heavens by the shaman along the celestial tree -- can be seen in the fact that the traditional symbology surrounding the Crucifixion of Christ quite clearly reflects the imagery surrounding the Osirian imagery of the Djed cast down and the Djed raised up.

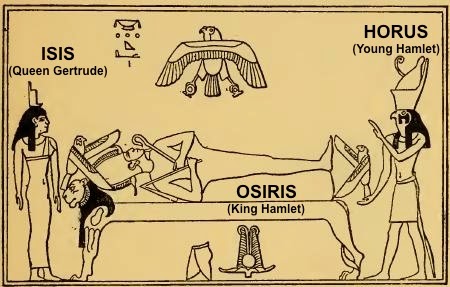

Below is an image from the temple of Seti I at Abydos which comes from a series of images depicting scenes from the myth-cycle of Osiris, Isis, Set and Horus. Specifically, the image shown below depicts Isis retrieving the casket containing the slain body of Osiris from the King of Byblos.

image: Wikimedia commons (link).

Significantly (as I discuss in some detail in my first book), the casket containing the body of Osiris had lodged in a tamarisk bush and then been concealed when the tamarisk grew into a tree around it, which the King of Byblos then cut down to use as a pillar in his palace, thus connecting the body of Osiris to the World-Tree which is cut down in many myths around the world (including to Yggdrasil, which ultimately cracks apart and falls at Ragnarokk) and thus to the unhinging of the world-axis and to the precession of the equinoxes.

This aspect of the story links the Djed-column (also called the "Backbone of Osiris") even more strongly to Yggdrasil and the sacrifice of Odin as alleged in the previous post -- and we can see that, sure enough, in the image above the column that the King of Byblos is handing over to Isis has the horizontal "vertebrae" lines that indicate it is a Djed-column and the Backbone of Osiris.

Although you may see or hear some people describe the image above from the temple of Seti I at Abydos as depicting the "raising of the Djed-column," it actually is not showing the raising of the Djed. In fact, it is showing the "bringing down" of the Djed and the corpse of Osiris, preparatory to his being laid in the tomb (in later scenes). Only later will Osiris be "raised up."

This fact is very important, because it is my assertion that the above scene is analogous to the taking down of the body of Christ from the Cross (sometimes called "the Descent from the Cross")!

If all the foregoing discussion and analysis is correct, and the myths from around the world (including those found in the Bible) are actually closely connected, and that they teach a shamanic message, and that they often use the absolutely central symbol of the Djed-column/Cruciform Cross/Ankh Cross/World Tree/Shamanic Pole to embody that message (a message of the "divine spark within" or the "Christ in you," as Paul phrases it), then the symbology of the "casting down" of the Christ into the tomb prior to his subsequent "raising up" is another manifestation of the same pattern, and the taking down of Christ from the Cross would parallel the taking down and giving to Isis of the Djed-column containing the corpse of the now-dead Osiris.

The imagery surrounding the Descent from the Cross supports this connection in absolutely breathtaking fashion. See, for example, this collection of images taken from art through the centuries of this event.

Even more striking, however, is the Christian art in the category known as Pietà and depicting the Virgin Mary holding the body of Christ after the Crucifixion.

Below is perhaps the most famous such Pietà, that by Michelangelo situated in the Vatican:

image: Wikimedia commons (link).

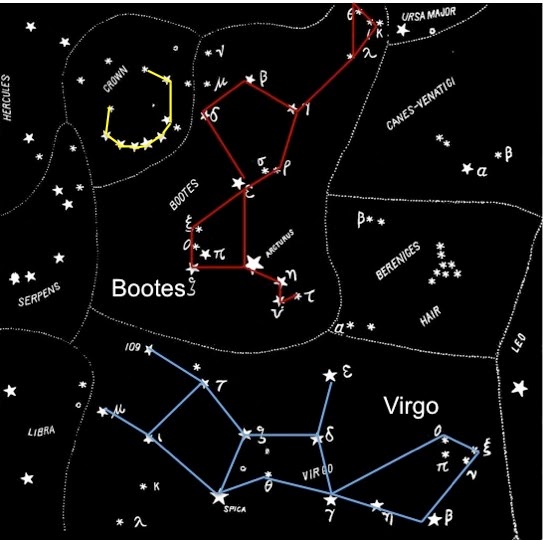

If we remember from previous posts that the "Djed cast down" corresponds to the horizontal line between the equinoxes, then the imagery of Isis and of Mary receiving the "cast down" or "nearly-horizontal" body of Osiris (ancient Egypt) and of Christ (New Testament) makes perfect sense: the sign of Virgo is positioned at the point of the fall equinox -- when the sun is declining down towards the grave, but just before the exact horizontal point of the equinox!

The "Virgo imagery" in both the above images (of Isis from the temple of Seti I, who died in 1279 BC and of the Virgin Mary from the work of Michelangelo who died in AD 1564) should be quite clear by now to anyone who has read The Undying Stars or looked at some of the images provided in previous posts about the constellation Virgo in the world's mythology (see for instance here, here, here, and here).

Specifically, look at the "outstretched arm" -- which is one of the most characteristic aspects of the Virgo constellation and which is embodied in ancient myth (and ancient art depicting Virgo-connected figures) over and over and over again. It is most evident in the image of Isis receiving the tilted (descending towards the horizontal) Djed-column from the King of Byblos, but the exact same outstretched hand is also present in Michelangelo's masterpiece:

Now that it is pointed out, you can see that the outstretched arm in the Isis image is over-elongated -- as if to ensure that you do not fail to notice it.

For those who may not be as familiar with the constellation Virgo (again, they can go check out the Virgo discussions above, or any of the others linked on this extensive index of constellations) and the way this constellation overlays on ancient sacred art, take a look at the image below from ancient Greece, circa 440 BC, depicting the Pythia: a priestess whose very role was to go into a trance or state of ecstasy in order to obtain knowledge from the other realm which could not be obtained in "ordinary reality." The outline of Virgo (with distinctive outstretched arm) is superimposed:

What does all this mean?

I would submit that it proves the connection of the world's ancient myths -- from ancient Egypt, to ancient Sumer and Babylon (who also had a central story of a "World-Tree" in the mighty cedar whose top reached to the heavens), to ancient India, to ancient Greece, to the myths found in the Old and New Testaments of the Bible, to the myths of the Norse, and the list goes on and on (to Africa, North and South America, the islands of the Pacific, Australia, east Asia . . . ).

It also proves the connection and close kinship of all these myths, their central symbology, and most importantly their esoteric message with each other and with the world's surviving shamanic cultures and traditions.

This connection suggests an even more radical and even more transformative ramification for what we have discovered above, because the esoteric and shamanic nature of the world's ancient wisdom-texts and traditions indicates that these teachings are meant to be put into practice by each man and woman who is incarnated in a body: by each man and woman who, these ancient scriptures teach, embodies a divine spark, a divine Thunderbolt, a divine "Christ within."

This evidence above suggests that it is part of our purpose here in this incarnation (perhaps even our central purpose) to recognize and to raise

that inner spark of divinity, that "vertical portion of the Ankh," that Djed-column which we each share with Osiris, along that central axis that inside the human microcosm reflects the celestial axis of the World-Tree found in the macrocosm.

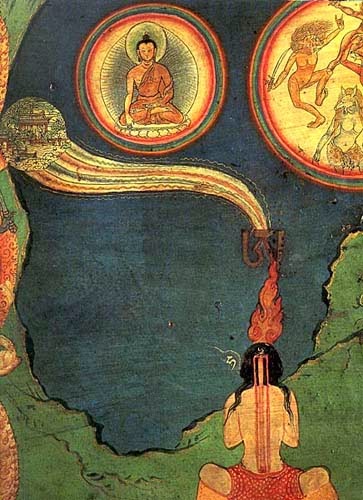

Perhaps this can be done through the practice of Yoga(whose name itself we have seen to be connected to the Ankh and hence to the Djed).

Perhaps this can be done through the practice of Kung Fu (whose name may also be related to the "name of the Ankh," and which is most definitely related to the precession of the equinoxes and the other celestial cycles which allegorize our divine spark cycling back upwards after first plunging downwards).

Perhaps this can be done through art and the creative force (as eloquently argued by Jon Rappoport, who connects that activity to the smashing of artificial realities embodied by trickster gods including Hermes, and by John Anthony West, who demonstrates that the ancient Egyptians appear to have had strong ideas about the transformative and consciousness-raising power of the artistic process of creating itself).

Perhaps this can be done through meditation, which science has shown can send the brain into a altered state -- perhaps even akin to a shamanic state -- when performed by those who have spent long hours practicing the discipline.

Perhaps this can be done through rhythmic chanting, which appears to have been a central component in the ancient wisdom and which amazingly seems to share a fairly similar form or pattern across many cultures and languages around the world.

Perhaps this can be done through the use of special plants and organisms such as mushrooms, which can be ingested or brewed into teas (please note the strong words of warning regarding the dangers of mistakenly consuming the wrong mushrooms posted on the website of mushroom expert Paul Stamets and repeated on this blog post here).

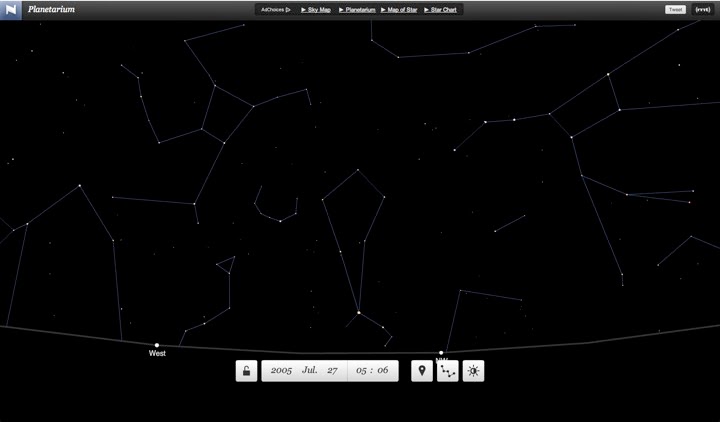

And certainly this can be done through the practice of what we commonly label as shamanic techniques (deliberately inducing states of ecstasy or the experience of non-ordinary reality, through a variety of methods available to humanity, including shamanic drumming): as we have seen, there is strong evidence to believe that all of the world's ancient wisdom was at one time shamanic, a fact which suggests that part of the world has been deliberately robbed of its shamanic heritage. In other words, the ancient myths were not intended to teach that Osiris "raised the Djed-column" so that we don't have to. The ancient myths were not intended to teach that Christ "raised the Djed-column" so that we don't have to. The ancient myths were not intended to teach that Odin "raised the Djed-column" so that we don't have to.

They contained those stories, and showed that pattern so many times, because it is what we are here to do.

image: Wikimedia commons (link).