Two previous posts have now demonstrated clear and detailed parallels between the use of the universal ancient system of celestial metaphor in the sacred stories from cultures on both sides of the broad Atlantic, specifically in the Norse myths of Scandinavia (also ancient Germania) and those of the Native peoples of North America (in this case the First Nations tribes inhabiting what is today Vancouver Island). To review those common elements, see "

Odin and Gunnlod" and "

The old man and his daughter."

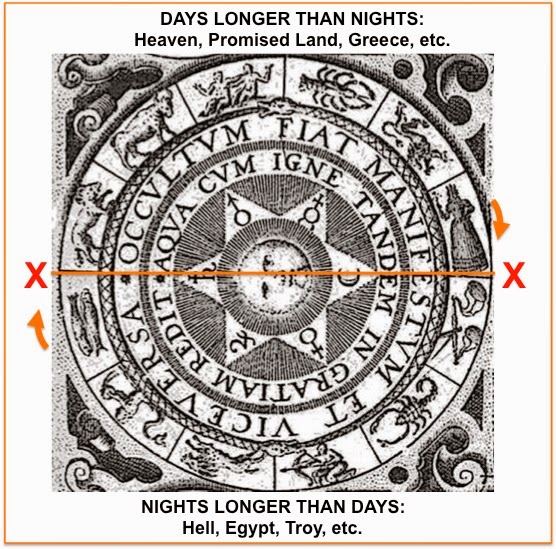

The purpose of demonstrating those clear and extremely specific details was to provide decisive evidence from mythology for an ancient system which spanned the globe. There is abundant evidence that this common ancient system is part of the universal sacred inheritance of all humanity -- an inheritance which was somehow transmitted to peoples living around the world, regardless of the distances which separated them. While the conventional "isolationist" counter is to argue that these common elements just coincidentally sprung up on their own, independently of one another, we saw evidence of extremely detailed and specific story elements -- such as the "clashing rocks" of the equinox, which are also found in the Greek myth of the Symplegades -- which are present in both the Norse and the Native American stories (in the guise of the Hnitbjorg in the Norse story, and the magical door which snapped open and shut on its own in the Native American story) and which cannot be explained away so easily by these isolationist "hand-waves."

We shall now examine clear evidence that the exact same pattern can be found in yet another culture separated by great distance and a mighty body of water -- this time, the Pacific Ocean. Because in the sacred traditions of ancient Japan, we find the same elements of the celestial metaphor played out once again -- this time in the important mythological story of Amaterasu, the sun goddess, when she decided to hide herself deep in a cave and plunge the world into darkness.

Giorgio de Santillana and Hertha von Dechend, the authors of the seminal 1969 book

Hamlet's Mill, treat this myth in some detail, and then state directly that it has clear parallels to a corresponding episode from Norse mythology. However, as is so often the case with that book (for whatever reason), they are rather "coy" in their discussion, now hinting about something that they will show you, and then slipping away without fully showing it to you (they do this constantly throughout the book, making it a somewhat tantalizing read . . . and re-read, and re-read, and re-read).

The myth that is the subject of this discussion is found (among other places in the sacred literature of Japan) in the

Kojiki, or "

Record of Ancient Matters," thought to be the most ancient extant Old Japanese sacred text. A translation of the Kojiki can be found

here. The authors of

Hamlet's Mill examine the myth of Amaterasu in chapter 11 of their text, a chapter entitled "Samson Under Many Skies." The entire text of

Hamlet's Mill can be

found online here; chapter 11 is

located here. In that chapter, the authors compare the characteristics of the Japanese god Susanowo to those of Samson (as well as of Ares and of Mars) -- Susanowo's name means "Brave-Swift-Impetuous-Male" (or, as translated in the version of the Kojiki linked above, "His-Swift-Impetuous-Male-Augustness") -- but we are more concerned here with a specific episode involving Susanowo's sister Amaterasu, the sun goddess, whose full name Amaterasu-omikame is translated as "Heaven-Shining-Great-August deity" in the version of the Kojiki linked above.

In order to understand the connections to the myth-patterns of other cultures (which are hinted at but not fully explained in

Hamlet's Mill), and to the universal system of ancient metaphor (which is discussed in greater detail in my most-recent book,

The Undying Stars), we will cite the entire episode from the Kojiki, prefacing that citation with the caution that the story is somewhat explicit (as is the episode from Norse mythology to which it is clearly related) -- so readers who might be uncomfortable with those details may want to stop reading here.

The following myth is from Part III, beginning at the section entitled "The Door of the Heavenly Rock-Dwelling." It follows immediately after the section entitled "The August Ravages of His-Impetuous-Male-Augustness" (that is to say, of Susanowo), in which we learn that His-Swift-Impetuous-Male-Augustness has impetuously violated all sorts of boundaries, breaking down the divisions of the rice-fields laid out by the Heaven-Shining-Great-August deity (his sister, the sun goddess Amaterasu), broken a hole in the top of Amaterasu's weaving-hall, and through it let fall a heavenly piebald horse, which he has flayed backwards (the very sight of which causes the women who are weaving the heavenly garments to perish in fright). We pick up the story at that point:

So thereupon the Heaven-Shining-Great-August deity, terrified at the sight, closed behind her the door of the Heavenly Rock-Dwelling, made it fast and retired. Then the whole Plain of High Heaven was obscured and all the Central Land of the Reed-Plains darkened. Owing to this, portents of woe all arose. Therefore did the eight hundred myriad deities assemble in a divine assembly in the bed of the Tranquil River of Heaven, and bid the deity Thought-Includer, child of the High-August-Producing-Wondrous deity, think of a plan, assembling the long-singing birds of eternal night [sometimes translated as crows or roosters] and making them sing, taking the hard rocks of Heaven from the river-bed of the Tranquil River of Heaven, and taking the iron from the Heavenly Metal-Mountains, calling in the smith Ama-tsu-ma-ra, charging Her Augustness I-shi-ko-ri-do-me to make a mirror, and charging His Augustness Jewel-Ancestor to make an augustly complete string of curved jewels eight feet long -- of five hundred jewels -- and summoning His Augustness Heavenly-Beckoning-Ancestor-Lord and His Augustness Great-Jewel, and causing them to pull out with a complete pulling the shoulder-blade of a true stag from the Heavenly Mount Kagu, and take cherry-bark from the Heavenly Mount Kagu, and perform divination, and pulling up by its roots a true

cleyera japonica with five hundred branches from the Heavenly Mount Kagu and taking and putting upon its upper branches the augustly complete string of curved jewels eight feet long -- of five hundred jewels -- and taking and tying to the middle branches the mirror eight feet long, and taking and hanging upon its lower branches the white pacificatory august offerings, and His Augustness Heavenly-Beckoning-Ancestor-Lord prayerfully reciting grand liturgies, and the Heavenly-Hand-Strength-Male deity standing hidden beside the door, and Her Augustness Heavenly-Alarming-Female [this is the goddess Ame-no-Uzume-no-Mikoto, sometimes simply referred to as the goddess Uzume] banging round her the heavenly clubmoss the Heavenly Mount Kagu as a sash, and making the heavenly spindle-tree her head-dress and binding the leaves of the bamboo-grass of the Heavenly Mount Kagu as a sash, and laying a sounding-board before the door of the Heavenly Rock-Dwelling and stamping, till she made it resound and doing as if possessed by a deity, and pulling out the nipples of her breasts, pushing down her skirt-string "usque ad privates partes" [for some reason this particular translator chooses to slip into Latin at that point]. Then the Plain of High Heaven shook, and the eight hundred myriad deities laughed together.

Hereupon the Heaven-Shining-Great-August deity was greatly amazed, and, slightly opening the door of the Heavenly Rock-Dwelling, spoke thus from the inside: "Methought that owing to my retirement the Plain of Heaven would be dark, and likewise the Central Land of Reed-Plains would be all dark: how then is that the Heavenly-Alarming-Female makes merry, and that likewise the eight hundred myriad deities all laugh?" Then the Heavenly-Alarming-Female spoke, saying: "We rejoice and are glad because there is a deity more illustrious than Thine Augustness." While she was thus speaking, His Augustness Heavenly-Beckoning-Ancestor-Lord and His Augustness Grand-Jewel pushed forward the mirror and respectfully showed it to the Heaven-Shining-Great-August deity, whereupon the Heaven-Shining-Great-August deity, more and more astonished, gradually came forth from her door and gazed upon it, whereupon the Heavenly-Hand-Strength-Male deity, who was standing hidden, took her august hand and drew her out, and then His Augustness Grand-Jewel drew the bottom-tied rope along at her august back, and spoke, saying: "Thou must not go back further in than this!" So when Heaven-Shining-Great-August deity had come forth, both the Plain of High Heaven and the Central-Land-of-Reed-Plains of course again became light.

After the sun goddess has come out from the "rock-dwelling," Susanowo is fined and punished (punishments include cutting his beard and pulling out the nails of his fingers and toes), a detail included here for the benefit of readers who are concerned that he should pay some penalty for causing so much trouble, although it does not concern the analysis which follows and which focuses primarily on the specific elements in common with the myths previously examined, those of Suttung and Gunnlod (from the Norse mythology) and of the old man and his daughter (from North America), as well as one other Norse myth which Hamlet's Mill mentions as being connected to this Japanese myth, without showing exactly why (see top of page 170 of Hamlet's Mill).

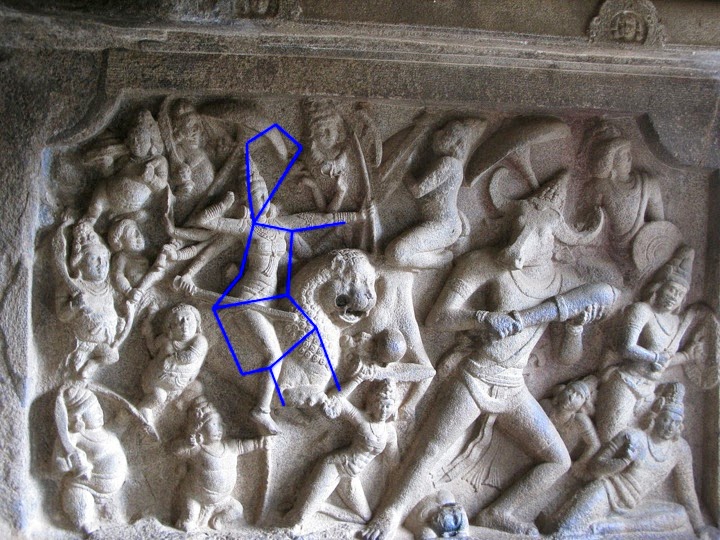

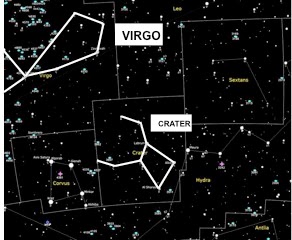

By now, readers should recognize the common elements: specifically, we have a goddess who represents the constellation Virgo (in this case, it is the goddess Uzume), and we have the presence of a "Heavenly Rock-Dwelling" with a door which can be "shut fast" behind the sun goddess. We have already seen in the two previous discussions that the important zodiac sign of Virgo stands at the very gate of the fall equinox, which was mythologized as a clashing door or clashing rocks through which the sun passes upon its course downwards towards the dark, winter half of the year -- and thus the Heavenly Rock-Dwelling with its shutting door in the Japanese myth clearly corresponds to the Hnitbjorg of Gunnlod, to the snapping door in the Native American story of the old man and his daughter, and to the Symplegades of Greek mythology (for readers who do not accept this clear connection, the significance of the Symplegades as a myth-metaphor for the equinox is treated in more detail in Hamlet's Mill on page 318).

But here in the story of Amaterasu and the dance of Uzume we have even more elements to examine, elements which parallel the myths from around the world and which argue strongly for the conclusion that a common system unites the ancient sacred traditions. Most striking, of course, is the method used to bring the sun goddess out of the rock. The authors of Hamlet's Mill describe it this way (refraining no doubt due to delicacy from adding the exact details of the dance of Uzume):

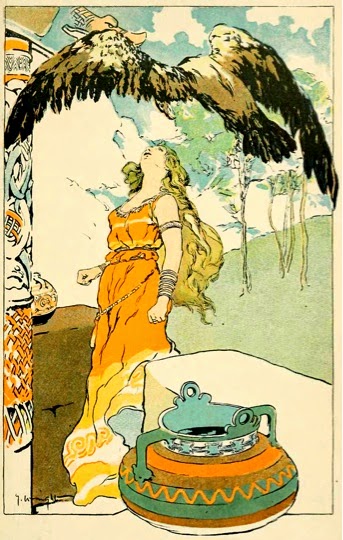

The 80,000 gods assembled in the Milky Way to take counsel, and at last came upon a device to coax the Sun out of the cave and end the great blackout. It was a low-comedy trick, part of the stock-in-trade that is used to coax Ra in Egypt, Demeter in Greece (the so-called Demeter Agelastos or Unlaughing Demeter) and Skadi in the North -- obviously another code device. 170.

They add a footnote about this dance, which states: "The obscene dance of old Baubo, also called Iambe in Eleusis, parallels the equally unsavory comic act of Loke in the

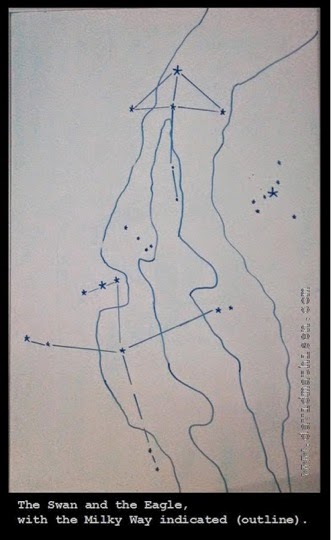

Edda. The point in all cases is that the deities must be made to laugh (cf. also appendix #36)." The "equally unsavory comic act" to which they refer is an episode from Norse myth involving Loki and Skadi. Skadi is the beautiful daughter of a jotun named Thjassi. The Aesir killed Thjassi when he was in the form of an eagle, pursuing Loki who was in the form of a falcon (clearly another myth related to the constellations

Cygnus and Aquila, discussed in the previous examination of the story of Odin and Gunnlod), by lighting a fire into which Thjassi flew and perished. As payment, Skadi was allowed to select a god from Asgard to be her husband, and also as part of the deal it was stipulated that the Aesir would have to make her laugh. Here is how that episode is recounted by Snorri Sturluson in his Younger Edda (and again, a caution to readers that this myth is equally as graphic as the Japanese myth to which the authors of

Hamlet's Mill compare it):

It was also in her terms of settlement that the Aesir were to do something that she thought they would not be able to, that was to make her laugh. Then Loki did as follows: he tied a cord round the beard of a certain nanny-goat and the other end round his testicles, and they drew each other back and forth and both squealed loudly. Then Loki let himself drop into Skadi's lap, and she laughed. Then the atonement with her on the part of the Aesir was complete.

This is from the Anthony Faulkes translation, London: Everyman, 1987 -- page 61.

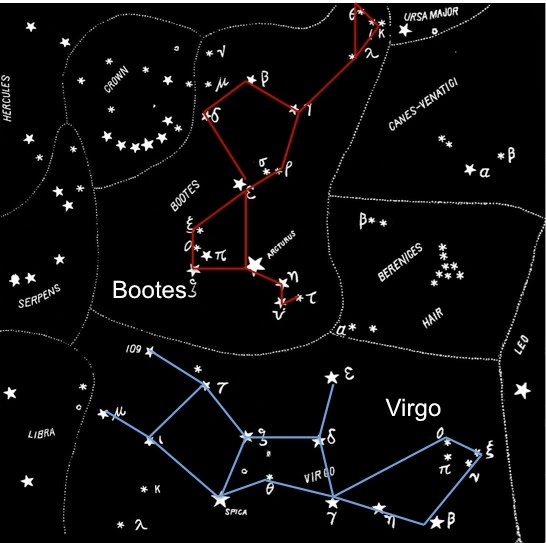

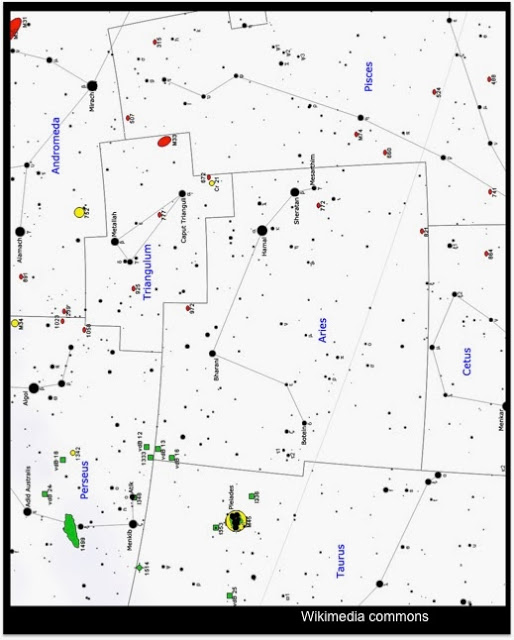

What on earth is going on here? The answer is that these are not stories about events "on earth" at all, but rather in the heavens. Once we realize that the goddess Uzume allegorizes the constellation Virgo, the connections will become clear. Below is a diagram of the constellation of Virgo, located in the sky just below the constellation Bootes the Herdsman, who can be seen to be smoking a rather long and prominent pipe (as depicted in the outlines suggested by

H.A. Rey, whose system for visualizing the constellations I believe to be by far the best). These connections between Uzume and Virgo are supported by the fact that in the Kojiki the goddess Uzume is described as binding together a sash or sheaf of bamboo grass with leaves, just as Virgo was depicted as holding a sheaf of wheat in some mythologies, as well as a sprig of laurel leaves in her manifestation as

the Pythia at the temple at Delphi. The connection is also reinforced by the presence of the crows or roosters mentioned in the Kojiki account, which are no doubt connected to the constellation

Corvus which is located next to Virgo. But we shall see even more astonishing connections momentarily.

The long pipe of the Herdsman constellation (Virgo's companion in many ancient myths) would appear to be the source of the sexual elements in both the myths (that of Uzume and that of Loki with Skadi). There is another female figure in Japanese mythology associated with Uzume, who is known as Otafuku, who is devoted to the goddess Uzume and who -- like Uzume -- is a fertility symbol in Japan and radiates an open and frank sexuality, as discussed in

this post from the website

Green Shinto (and which cites a discussion on the subject by Hirata Atsutane, who lived from 1776 to 1843, and who cites older sources to support the connection between Otafuku and Uzume). Otafuku is shown in the nineteenth-century Japanese painting below, along with a character known as Daikoku, who is holding over his head a large gourd which clearly resembles the head and pipe of Bootes (depicted in the star chart to the right, along with Virgo):

As she is depicted, Otafuku is dancing with one hand on her hip and the other extended and holding a wand. Her posture is clearly illustrative of the constellation Virgo, right down to her two feet and the angle of her body. See the diagram below, in which the outline of Virgo has been superimposed:

But that's not all: Otafuku (who is associated with Uzume) is often depicted with a red-faced companion named Sarutahiko, who is

described here in the blog

More Glimpses of an Unfamiliar Japan as a "phallic kami" (kami are the heavenly beings described in the Kojiki), possessed of a long, red, upturned nose. His mask, that blog tells us, "is often paired with Uzume/Otafuku."

Now, why should Uzume/Otafuku be paired with a kami who has an unusually long nose which is upturned at the end? Take a look again at the diagram of the constellations Virgo and Bootes, above, and the answer will immediately become clear.

The sexual aspect of these two constellations may seem obvious now that it has been demonstrated, but I would venture to argue that it is not obvious at all, and that the vast majority of the readers of this blog could have gone their entire lives looking at the stars, or at charts showing Virgo and Bootes, and never thought of them as depicting any "off-color" or sexually-explicit "low comedy" (as the authors of Hamlet's Mill phrase it) whatsoever. In fact, many readers may even be shocked that anyone would. And yet we see that this connection was apparently part of the ancient universal system of celestial metaphor, and that it shows up quite dramatically in the myths of both ancient Japan and of the Norse (and, as the authors of Hamlet's Mill point out, in the myths of ancient Egypt and ancient Greece as well).

The long upturned pipe of the constellation Bootes the Herdsman points right to the handle of the Big Dipper, which was also anciently known as the Wain or wagon of the sky, which in Norse myth is sometimes pulled by goats (Thor's wagon is famously drawn by goats). No doubt this explains the graphic slapstick comedy routine enacted by Loki, who in this particular case is playing the part of Bootes (but this time it isn't a nose which is represented), and who eventually lands in Skadi's lap (you can see how this could happen by referring again to the star-chart of Bootes and Virgo).

The obscene dance of Uzume (which is paralleled by the obscene actions of Baubo in Greek myth, some descriptions of which can be found

here) in which she pulls down the belt of her skirt can also be clearly understood from the diagram of Virgo in the chart above, where the line of her skirt is depicted as running between the two bright stars of

Spica and

Zeta Virginis.

Other clear indicators in the Kojiki which alert us to the fact that the story relates to Virgo and the surrounding constellations include the description of the "string of curved jewels, eight feet long" (this is almost certainly the curved arc of the Northern Crown, which can be seen in the chart above just above and to the left of Bootes the Herdsman) and the seemingly-random inclusion of the shoulder-blade of a stag (the connection between a stag and Virgo is also found in myths around the world, and is explained in part in the first three chapters of

The Undying Stars which are available to

read on the web here). The connection to Virgo is also reinforced by the description of the mirror (which is also eight feet long).

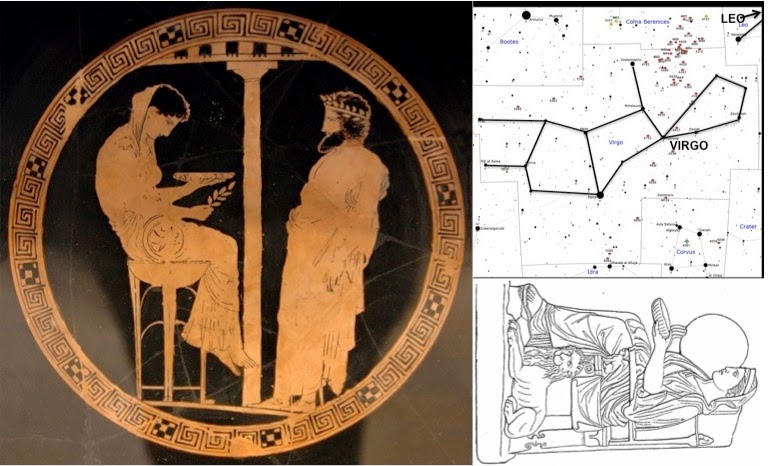

I submit that this mirror represents the faint oval circle of stars which can be seen in front of the face of Virgo and above her outstretched arm -- I have drawn a red oval around them in the diagram below:

I argue that this roughly circular grouping was depicted in ancient Greek myth as the round plate of holy water depicted in the famous portrait of the Pythia at Delphi shown in the diagram below. Notice that the ancient artist (from the fifth century BC) has located the round platter or shallow basin of water just above the outstretched sprig of laurel in the depiction -- just as the glimmering oval of stars circled in the diagram above are located above the outstretched arm of the constellation. Note also in the diagram below, at bottom right, that the depiction of the goddess Rhea, who is seated upon a throne and who also has one hand out forward, is shown holding some sort of circular object above this outstretched arm. The fact that she is related to the constellation Virgo is further reinforced by the lion crouching at her feet: Virgo follows Leo the Lion in the zodiac procession.

But perhaps the most important aspect of the story is the element of laughter, which the authors of Hamlet's Mill single out as being critical in the footnote from page 170 cited above. The risque dance of Uzume has the effect of making the assembled kami all roar with laughter, and causes the astonished Amaterasu to open the door of her rock-cave and peek out. The obscene actions of Baubo bring a smile to Demeter's face. The ridiculous antics of Loki cause Skadi to smile as well, something she thought the Aesir could never make her do. What is the meaning of all of this? The authors of Hamlet's Mill do not tell us, although they indicate that it is "the point in all cases" of this myth as it is found around the world.

The answer can again be found, I believe, by looking to the book of the stars. There you can see that Virgo's head contains two rather faint stars which, if connected, clearly make the goddess appear to be smiling:

And now the identification with Virgo in all the myths across the centuries and across the two mightiest oceans on the planet is complete!

But one more thing remains to be noted, and it may have already suggested itself to readers familiar with the stories of the Old Testament, and that is the fact that there is a female character in the stories of Genesis who is described as perennially beautiful and who is also famous for laughing: Sarah, the wife of the patriarch Abraham. This incident is described in Genesis 18:12-15, where we read:

Therefore Sarah laughed within herself, saying, After I am waxed old shall I have pleasure, my lord being old also?

And the LORD said unto Abraham, Wherefore did Sarah laugh, saying, Shall I of a surety bear a child, which am old?

Is anything too hard for the LORD? At the time appointed I will return unto thee, according to the time of life, and Sarah shall have a son.

After her son Isaac is born, Sarah then laughs with joy. In Genesis 21:6, we read: "And Sarah said, God hath made me to laugh, so that all that hear will laugh with me."

Now, the point of bringing in this Bible story is not to "put down" the sacred scriptures of the Old or New Testaments, as discussed in this previous post entitled "

The ancient torch that was lighted for our guidance." It is my conviction that all the sacred scriptures of humanity are a priceless inheritance, and that they are all intended to convey

an esoteric message of profound importance and transformative power. When we see that this particular Old Testament story follows the very same universal system of celestial metaphor, we should realize that those who have sought to denigrate the mythologies of the rest of the world as "pagan" and to elevate the scriptures of the Old and New Testament as "historical" and "literal" (as opposed to esoteric) and therefore different from all the other ancient sacred traditions of humanity, are either making a profound error or perpetrating a great deception (and one which has led to the wholesale destruction of much of the world's ancient wisdom and the deliberate suppression and even eradication of many of the sacred texts which had preserved that wisdom through the millennia).

I provide many more explanations and examples of how the stories of the Old and New Testament follow this same world-wide system of celestial metaphor in The Undying Stars. Further, I explore the profound esoteric message that I believe this system may have been intended to convey to humanity. The fact that this system was intended to impart profound knowledge to men and women is very clear from the underlying content of the two "Virgo" stories we have examined prior to this one: in each, divine wisdom is imparted to humanity (the marvelous mead in the Norse myth of Odin and Gunnlod, and the gift of "heavenly fire" in the Native American myth of the old man and his daughter).

In the story above of Amaterasu and the dance of Uzume, the connection to the imparting of divine wisdom to humanity is not so apparent, but it is in fact present. It has to do with the fact that Uzume's dance is described as being that of one who acts "as if possessed" -- in other words, she is in a state of ecstasy, the central importance of which has been discussed in previous essays

such as this one. In his 1983 text

Audience and Actors: A Study of their Interaction in the Japanese Traditional Theater, Jacob Raz examines the importance of the dance of Uzume. On page 11 of that work, he tells us:

About the dance we are told in the Kojiki that "as if possessed, (she) plucked at her nipples and pushed the belt of her skirt down to her private parts . . ." The eight hundred myriad kami laughed heartily to see the dance. The Nihonshoki uses the term wazaogi for the dance. Wazaogi means 'mimic' or imitative dance or gesture. This interprets the dance as a dramatic performance. The Kojiki includes also simple conversation, a "divinity inspired utterance" and even a simple plot. The Nihonshoki adds that Ame-No-Uzume was the ancestress of Sarume-No-Kimi (literally, Monkey-Female), a family of professional shamanesses, (in Japanese, miko), in the early period.

He goes on to say:

First, the story is thought to have been a description of a shamanic dance. Ame-No-Uzume, by means of an ecstatic dance, stamping on the tub and helped by the cheers of the myriad kami and by her own divinely inspired utterance, is actually summoning a divine spirit and is eventually possessed by it and transfers it to Amaterasu. By this interpretation, the Sun Goddess not only is in a stage of rage but is also suffering from a kind of ailment. Ame-No-Uzume is her healer, and the act is a kind of magico-medical treatment. 11.

I believe that the close examination of the sacred story of Amaterasu and Uzume in Kojiki reinforces these conclusions, and provides further powerful evidence that this system spanned the globe, appearing in Japan, in the Americas, in the lands of far northern Europe, in the mythologies of ancient Greece, ancient Egypt, ancient Sumer and Babylon, and further east into India and China and the lands of Asia where shamanism survived into the modern period, as well as in Australia, New Zealand, and the scattered islands of the vast Pacific. I believe this examination should also go a long ways towards demonstrating that the exact same system of celestial metaphor was operating in the stories of the Old and New Testaments as well.

This is a conclusion which, if correct, has tremendous ramifications for our understanding of human history, and one which has staggering implications for every man or woman alive today.