Here in California it is still January 18, and I am still continuing the direction of thought from the previous post honoring Huo Yuanjia.

Huo Yuanjia's achievement in founding the Jingwu Athletic Association in 1909 cannot be underestimated. In their 2010 book Jingwu: The School That Transformed Kung Fu, authors Brian Kennedy and Elizabeth Guo demonstrate that the establishment of this school marked a significant change in the way that kung fu was taught, one that would reverberate to this day, and one with very important implications.

They write:

The first public martial arts school where one could just walk in the door, pay a fee, and sign up was the Jingwu Association, which opened in 1909 and ushered in a new era in Chinese martial arts training. The Jingwu's most influential time ran from 1909 to 1924. The founding of the Jingwu Association, with its focus on "walk in, sign up, and learn Chinese martial arts as a form of exercise and recreation" marks the single most important turning point in Chinese martial arts -- the transition from being a manual trade associated with the military, militias and bodyguards to being a form of cultural recreation.

In fairness, it should be mentioned that there were other privately funded martial arts groups in China who were doing the same things that the Jingwu Association was doing. But these other groups, for whatever variety of reasons, were all short-lived and not particularly influential. 3.

Earlier in the book (page x), they noted the other significant "firsts" that the Jingwu Association should be credited with:

- The first public Chinese martial arts training facility.

- The first to teach Chinese martial arts as a sport or recreation.

- The first to place women's programs on an equal footing with men's programs.

- The first to use books, magazines and movies to promote Chinese martial arts.

In other words, Huo Yuanjia's vision (and by all accounts he was central in the founding of the Jingwu Association) in large part created the transition to the way we think of martial arts training today, a vision that clearly established four aspects still very much present in the landscape around the world to this day.

In short, I believe it is no great stretch to deduce that Huo Yuanjia and his fellow founders of this new association believed that martial arts are an important aspect of life, one that goes along with other forms of learning. In fact, as Brian Kennedy and Elizabeth Guo inform us, the Jingwu Association was not only devoted to training its members in the martial arts, but in providing other forms of learning, including "cerebral activities" including playing chess and learning from books (xi). In other words, its founders clearly saw a connection between the mental and physical disciplines and the importance of each.

In short, I believe it is no great stretch to deduce that Huo Yuanjia and his fellow founders of this new association believed that martial arts are an important aspect of life, one that goes along with other forms of learning. In fact, as Brian Kennedy and Elizabeth Guo inform us, the Jingwu Association was not only devoted to training its members in the martial arts, but in providing other forms of learning, including "cerebral activities" including playing chess and learning from books (xi). In other words, its founders clearly saw a connection between the mental and physical disciplines and the importance of each.

If you study the martial arts, it may be of some interest to think that Huo Yuanjia seems to have wanted you to be able to have the opportunity to do so, and to have believed that such an opportunity is as important to human development as any other form of learning.

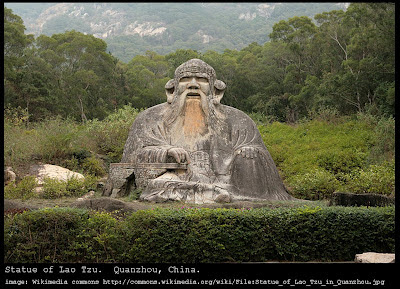

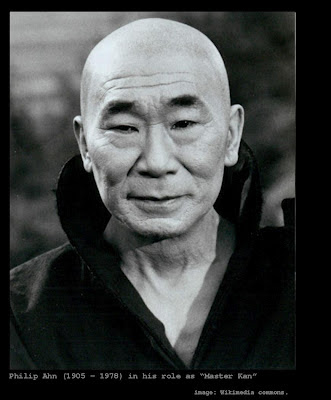

In any event, it is also noteworthy that the movie Fearless (2006), which features Jet Li as Huo Yuanjia, takes its name from a line in the Tao Teh Ching of Lao Tzu (33):

Mastering others is strength --

Mastering yourself makes you fearless.