We recently published two posts (

here and

here) discussing the awe-inspiring voyages of the Polynesian Voyaging Society's traditional double-hulled ocean-going canoe

Hokule'a and the nearly-lost navigational techniques they use to travel thousands of miles across the open sea using the stars, the sun and moon, and the subtle directional clues provided by the ocean swells, the colors of the sky and sea at sunrise and sunset, and the activities of marine wildlife and birds.

Polynesian Voyaging Society President and

Hokule'a wayfinder Nainoa Thompson learned these traditional techniques from master navigator

Mau Piailug (1932 - 2010), and he graciously explains some of the outlines of that ancient wisdom on the PVS website and passes it along in person to new students of the craft who participate in the ongoing voyages of

Hokule'a.

On this page, entitled "

The Celestial Sphere," the PVS explains the celestial mechanics of the circling stars, as well as the celestial mechanics of the paths of the sun and moon throughout the year. It is well worth studying and understanding, and is explained clearly and with excellent diagrams. As explained on that page, an observer at the north pole, looking up at the night sky, would see the entire celestial sphere turning around a point directly overhead (see diagram below).

The north star, marked in the diagram above by a star, would not appear to move (actually, because it is just slightly off of the exact true celestial north pole, it would move in a tiny circle, but for purposes of this discussion it can be understood to mark the celestial north pole and thus to remain stationary while the rest of the sky appears to turn). However, stars that are located some angle away from the north celestial pole would appear to trace out a circle around the celestial north pole as the earth turns. These circles are marked in the diagram above as blue circles with arrows indicating the direction of the star's apparent daily motion (opposite to the direction of the earth's rotation).

The Polynesian Voyaging Society, however, does not typically sail across the north pole, but rather through the Pacific latitudes north and south of the equator. To an observer sailing across the equator, the apparent motion of the stars in their courses would be quite different than to our observer sitting at the north pole. Below is a diagram of the courses of the stars at the equator.

In this image, the surface of the ocean upon which the observer is sailing has been added as a light-grey disc. The north celestial pole and the north star are now located on the horizon at due north (left in this diagram and marked with the north star). The south celestial pole is similarly located on the horizon at due south (not depicted on the diagram above). The courses of the stars will now be perpendicular circles, but half of these circles will take place below the horizon. As the earth turns, the stars will appear to rise out of the eastern horizon in vertical courses, arc overhead, and descend on vertical courses to the western horizon, where they will again disappear.

We can now understand how an expert navigator who knows the stars could set his vessel's course by lining up known sight-marks on the beam of his vessel with a known rising star. If he were exactly at the equator, for example, and wanted to head due north, he could sight to a star known to occupy declination 0° (along the celestial equator) and keep it 90° to his course, thus pointing his prow due north. He could use such a star even after it had risen many degrees in the night sky, because he knows it rises perpendicular to the horizon and thus he can mentally trace its course back down to the horizon and use it for many hours as a guide. If he wanted to take a heading some degrees west of due north, he could sight to a star along the celestial equator but place it those same number of degrees further than 90° to his starboard beam, thus turning his prow west of north by that number of degrees (or, as described on

this webpage, within one of 32 headings of 11.25° degrees each, each of which can also be divided for even greater precision).

Likewise, if he knew of a star that was at declination +19° (which is to say, 19° on the north side of the celestial equator) and he did not have a star along the celestial equator to use, he could still orient his vessel due north by lining up that star's rising point 19° forward of due east (or at 81° in his mental compass). If he desired a heading that was west or east of north by some number of degrees, he would simply make the desired adjustment to the alignment that he kept that star.

Between the north pole and the equator, the stars in their courses will not rise perpendicularly out of the ocean as they do at the equator, nor will they make circles in the sky parallel to the horizon as they would at the north pole. Instead, the north celestial pole will be tilted by the same number of degrees that the observer is north of the terrestrial equator. In the diagram below, the observer has proceeded north from the equator to a latitude of about 30° north, and because he is going towards the north star it is rising up out of the ocean as he proceeds north (remember that it was on the horizon at due north when the vessel was at the equator). As it rises up, the stars in their courses which appear to circle the north celestial pole due to the rotation of the earth will still trace out perfect circles, but these circles will now be tilted as indicated in the diagram.

The navigator could still set his course by a star rising along the celestial equator or rising at a known declination on either side of that celestial equator (such as our star tracing a circle at a declination of 19° on the north-star side of the equator), but he must remember that the star no longer rises perpendicularly as it did at the equator, so as it climbs higher in the night sky he must mentally draw it back to the horizon at an angle corresponding to his vessel's northerly latitude.

All of this fascinating detail is described on the Polynesian Voyaging Society website page discussing the Celestial Sphere and also on this page entitled "

Holding a Course."

Perhaps the most fascinating detail of the techniques that Nainoa Thompson uses is described on the page entitled "

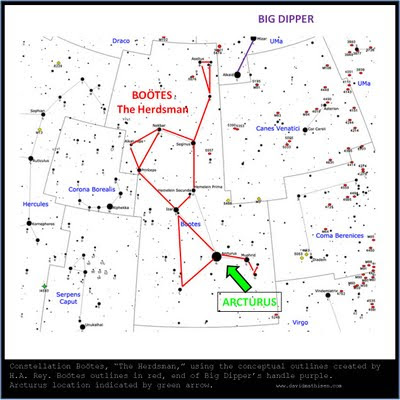

Hawaiian Star Lines and Names for Stars." There, the text explains that, "To help remember the pattern of stars in the sky, Nainoa Thompson has organized the sky into four star lines, each line taking up about one fourth of the celestial sphere." These star lines are quadrants of the celestial sphere like the wedges of an orange cut into four equal wedges. As the earth turns, these wedges or star lines -- each containing recognizable constellations such as Orion or Scorpio or the Great Square of Pegasus -- rise up out of the eastern horizon and then move overhead, setting later into the western horizon.

What is so fascinating about this mental construct created by Nainoa Thompson is the fact that it sheds some light on the very ancient practice of dividing up the celestial sphere, a practice dating back at least to the very ancient Babylonian mythological records from around 1700 BC (and perhaps even earlier than that, if you believe there was an advanced civilization which bequeathed its knowledge to the ancient Sumerians, Babylonians and dynastic Egyptians, from whence that knowledge was passed on to other successive cultures including the Greeks and the Celts and others).

In Appendix 39 of the indispensable if often-mysterious treatise

Hamlet's Mill: An Essay on Myth and the Frame of Time, by Giorgio de Santillana and Hertha von Dechend (1969), the authors discuss the division of the celestial sphere found in ancient mythology. There, they explain that in the Babylonian creation epic known as

Enuma Elish, we learn at the

end of the Fourth Tablet and beginning of the Fifth Tablet that Marduk / Jupiter surveyed the heavens and the earth and divided up the world, and specifically that he made "Anu, Enlil, and Ea" to occupy their places, and that he "founded the station of Nebiru to determine their (heavenly bands)" in the translations cited by de Santillana and von Dechend (430 - 431).

Later, the authors explain that these "ways of Anu, Enlil and Ea" were divisions of the celestial sphere, bands running parallel to the celestial equator rather than dividing it up like a quartered orange the way Nainoa Thompson does. Each of these ancient Babylonian celestial bands was approximately thirty degrees wide:

The "Way of Anu" represents a band, accompanying the equator, reaching from 15 (or 17) degrees north of the equator to 15 (or 17) degrees south of it; the "Way of Enlil" runs parallel to that of Anu in the North, the "Way of Ea" in the South. 434.

Using the spheres in the diagram above, in which the largest circle represents the celestial equator, the reader can easily envision these ancient "ways" dividing up the celestial sphere. Later, the authors discuss this concept even further, and tie it explicitly to the great navigators of Polynesia:

Mesopotamia is by no means the only province of high culture where the astronomers worked with a tripartition of the sphere -- even apart from the notion allegedly most familiar to us, in reality most unknown -- that of the "Ways" of Zeus, Poseidon, and Hades as given by Homer. The Indians have a very similar scheme of dividing the sky into Ways (they even call them "ways"). And so have the Polynesians, who tell us many details about the stars belonging to the three zones (and by which planet they were "begotten"); but nobody has thought it worth listening to the greatest navigators our globe has ever seen; nor has any ethnologist of our progressive times though it worth mentioning that the Polynesian megalithic "sanctuaries" (maraes) gained their imposing state of "holiness" (taboo) when the "Unu-boards" were present, these carved Unu-boards representing "the Pillars of Rumia," Rumia being comparable to the "Way of Anu," where Antares served as "pillar of entrance" (among the other "pillars": Aldebaran, Spica, Arcturus, Phaethon in Columba). 436-437.

The fact that this was all written and published before the rediscovery of the non-instrument navigation techniques that had been preserved among the people of Satawal and before the first voyage of

Hokule'a on which Mau Piailug was the navigator is noteworthy -- it indicates that the authors of

Hamlet's Mill were onto something, although they could not know it.

The fact that Nainoa Thompson has found it useful to divide the sky up into four "star lines," much the way the ancients including the ancient Polynesians divided up the sky into three "ways" is equally significant, and indicates that the ancient mythologies may well have preserved knowledge that was used for open-ocean non-instrument navigation as well.

In fact, it is quite clear that the wisdom and ocean lore preserved by Mau and his ancestors, and passed on to Nainoa Thompson and the other members of the Polynesian Voyaging Society -- where it is still used to great effect on amazing deepwater voyages across the mighty Pacific and beyond -- may be one of the most significant pieces of ancient wisdom that somehow survived through the ages (even though it came very close to dying out).

It can provide a window onto mysteries of mankind's ancient past that we might never have otherwise understood, or might have only been able to guess at without practical testing. Whether or not one believes that there may have been actual ancient contact between people who are traditionally thought to have been isolated by the mighty oceans is actually less important than the fact that such understanding of and division of the celestial sphere is clearly very handy for those who venture out into the great deeps in traditional vessels without modern instruments. Where it appears in other ancient cultures, we might suspect that some form of similar navigational skills might also have accompanied the celestial knowledge that was preserved in those traditions.

In this way, it appears that all of mankind owes the Polynesian Voyaging Society, and Mau Piailug and Nainoa Thompson, a tremendous debt of gratitude and respect.