In the previous post, we examined Plutarch's twin discourses "

On the Eating of Flesh," in which the ancient philosopher and priest put forth several powerful arguments (in vivid and graphic language) against the consumption of animal meat for food.

We saw that in his opening sentences, Plutarch "turns the corner" on those who ask what could have inspired Pythagoras (who was famously vegetarian according to tradition and according to the Pythagorean school of philosophers who followed his hallowed teachings) to abstain from eating plants, by asking (and I paraphrase) "you should instead ask what came over some deluded and misguided human to begin eating meat in the first place!"

Such a response argues that it is the eating of meat which is the aberration, and the plant-based diet which is the norm. It was certainly designed to startle Plutarch's ancient listeners, just as it startles modern readers, who take the consumption of meat for granted much like Plutarch's audience apparently did, although perhaps for different reasons.

According to modern dogma, mankind evolved from primitive "hunter-gatherers," whose nomadic lifestyle involved following game animals from one place to another, until mankind finally figured out agriculture and settled down to enjoy the consistent diet of grains that it produced to supplement the original meat-based plan. Believers in this modern orthodoxy would probably say that Plutarch was woefully ignorant of the fact that hunting for meat came first, and that his rejoinder to the question of eating flesh is completely incorrect.

They would say that eating meat was part of the earlier diet, and that vegetarianism (such as Pythagoras taught) was a more recent development, in contrast to Plutarch's assertion that vegetarianism is normal and eating meat a later abnormality. He was too ignorant to be aware of mankind's long history of primitive hunter-gatherer existence.

A

hunter-gatherer or

forager[1] society is one in which most or all food is obtained from wild plants and animals, in contrast to

agricultural societies which rely mainly on

domesticated species.

Hunting and gathering was the ancestral

subsistence mode of

Homo, and all

modern humans were hunter-gatherers until around 10,000 years ago. Following the

invention of agriculture hunter-gatherers have been displaced by farming or

pastoralist

groups in most parts of the world. Only a few contemporary societies

are classified as hunter-gatherers, and many supplement, sometimes

extensively, their foraging activity with farming and/or keeping

animals. The earliest humans probably lived primarily on

scavenging, not actual hunting. Early humans in the

Lower Paleolithic

lived in mixed habitats which allowed them to collect seafood, eggs,

nuts, and fruits besides scavenging. Rather than killing large animals

themselves for meat, they used carcasses of large animals killed by

other predators or carcasses from animals that died by natural causes. [Wikipedia, "

hunter-gatherer," as accessed on November 19, 2012].

Of course, the above assertions describe one possible theory of mankind's ancient past, and the evidence in their favor should be carefully considered and weighed against other possibilities, but they are by no means completely certain, regardless of the confident (or even arrogant) tone in which they are usually presented to the reader of college or high-school textbooks (and online encyclopedia services).

If all modern humans were hunter-gatherers until around 10,000 years ago, then Plutarch is completely incorrect in saying that the one who first "touched his mouth to gore and brought his lips to the flesh

of a dead creature" was the aberrant one. According to the above assertions, domesticated grains and animals came later, but they only replaced the consumption of wild plants and animals, whether those animals were the scavenged carcasses killed by other predators, or fresh kills hunted down by the humans themselves.

Plutarch implies that the first taste of meat was an "accident" introduced into the normal diet of abundant grains and fruits offered by Demeter and Dionysus, but those who accept the hunter-gatherer dogma concerning mankind's ancient past must believe that Plutarch was sadly ignorant and therefore completely deluded and mistaken.

In fact, there is now an entire lifestyle and dietary plan built around returning to the eating habits of this imagined pre-agricultural human past, called the "

Paleo Diet," which is billed as the "healthiest diet" and one which "mimics the diets of our caveman ancestors." Based on the supposed food supply of those "hunter-gatherer ancestors" who lived between 2.6 million years ago and the beginning of the agricultural revolution, it embraces fresh meats and "fresh fruits, vegetables, seeds, nuts, and healthful oils."

Since those who believe in this evolutionary narrative of mankind's past do not typically believe in the reincarnation of the soul (if they believe in the existence of the soul at all or its continuation after the death of the body), they are probably not greatly swayed by Plutarch's concerns (citing other ancient philosophers) that the possibility of reincarnation (or, as Plutarch puts it, "the migration of souls from body to body") should make us hesitant to slay other sentient creatures for food when we have abundant plant-based food available that does not involve the shedding of blood to obtain.

The supporters of this newly-popular "Paleo diet" also do not seem to consider the possibility that the entire "hunter-gatherer" narrative might be a mistaken fabrication of modern Darwinian mythology. In other words, there is at least as much evidence that suggests that ancient civilizations did not arise through a process of stumbling towards domestic plant and animal foods but rather by a process that completely confounds the entire foundation of modern evolutionary anthropology.

For example, in her book

Approaching Chaos (discussed in previous posts such as "

The shamanic tradition in ancient Egypt," "

Stonehenge acoustics, and beyond," and "

Arkaim, gold, and the ancient shamanic rituals") Lucy Wyatt presents arguments that domesticating crop grains and cattle, sheep and goats would have taken so many years of deliberate and sophisticated and directed breeding that hunter-gatherers would probably have abandoned the project long before they ever got to a workable semblance of domesticated plants or animals. She also presents convincing evidence that the neolithic lifestyle would have been significantly

more difficult than nomadic hunter-gathering, not less.

Beginning on page 48 of her book, she writes:

It would be interesting to know whether anyone has recently tried to naturally 'evolve' wild grasses into something approaching modern cereals. How many seasons would you have to wait before einkorn (a form of early wheat) began to taste vaguely of wheat and become useful as a food staple? Even more suspicious is the fact that what defines a cereal as domesticated is not so much the taste but the hallmark of civilization, namely convenience in harvesting and sowing.

In terms of cereal, the genetic change is in the germination of the seed and in the rachis, the hinge between the seed head and the stalk. In the wild plant the rachis is brittle and breaks easily in the wind, allowing the plant to spread its seeds as soon as it is ripe. A domestic version with a stronger rachis waits for the harvester to pick it. Likewise, a domestic seed waits to be sown before germinating. [. . .] One expert in this area, Gordon Hillman, has calculated that the rare genetic mutant, the seed head without a brittle rachis, has a probability of occurring only once or twice for every '2-4 million brittle individuals' and that it would then take 20 cycles of harvesting for these non-brittle seed heads to finally dominate the crop [Miten, 2004, pp36-37]. Given the rarity of these seed heads, why would anyone bother to wait, especially with hungry families to feed? 48-49.

You can read more of Lucy's discussion of this practical problem to the modern fable of man's supposed transition from millenia of hunter-gathering to domestication of grains in an article she published

here on the Graham Hancock website.

Similarly, Lucy points out the difficulties with the breezy narrative describing the supposed domestication of wild animals during the transition from paleolithic to neolithic:

The domestication of animals was as strange as the modification of cereals. Not only did animals change shape -- as prehistorian Steve Mithen points out [Mithen, 2004, p34]: 'All animal species become reduced in size when domesticated variants arise' -- but they also became conveniently and usefully docile. Is evolution capable of producing the necessary change in the fundamental nature of an animal, even if a cow is still recognizably related to an auroch (considered to be the precursor to a cow)?

Anyone who claims that farm animals evolved out of tamed wild ones has clearly never worked with animals. Taming might conceivably work with a jungle fowl having its wings clipped and being bred into a chicken -- although even a chicken can be vicious -- but not with a cow, let alone a bull or a horse. Even domesticated modern versions of these larger animals are still capable of killing a person and demand enormous respect. They are too powerful and dangerous to be capable of being bred in captivity from wild and then turned into the sufficiently docile creatures necessary for farming.

If domestication was so easy, why has the zebra never been domesticated? [. . .] Even Julius Caesar knew that wild aurochs could not be tamed [Fagan, 2004, p156]. So how can one believe the nonsense that hunter-gatherers managed to tame aurochs because they 'culled more intemperate beasts and gained control of the herd' when they came into close contact with them during droughts? [Fagan, 2004, pp157-158].

If it really was possible to tame wild animals simply by penning them, over how many generations would it take for them to become no longer wild? Why would anyone wait to find out? Surely, if you breed a wild animal with more of the same species, the result is still wild? [. . .]

There is of course the usual 'chance mutant gene' explanation. We are given the impression that, around the time of these early experiments Stone Age man was able to spot a genetic variation in the wild herds he followed and was capable of realizing that a particular animal was carrying a mutant gene that one day would make a 'useful cow.' But while we might know what would make a 'useful cow,' how could Stone Age man know what the desired outcome was? How suspicious that the outcome was so convenient and so useful. 49-51.

These objections should indicate that any reflexive dismissal of Plutarch's assertion that vegetarianism is in fact mankind's original diet and that meat came later, based on what our school masters tell us about mankind's supposed ancient hunter-gatherer timeline, may be overly hasty.

Similarly, the Wikipedia assertion (which only echoes the modern dogma published in current academic texts on the subject) that "all modern humans were hunter-gatherers until 10,000 years ago" certainly runs into problems when it tries to grapple with the abundant evidence attesting to the incredible achievements of the ancient Egyptians, whose civilization apparently popped up right out of these endless millennia of nomadic hunter-gathering and started creating monuments evincing mathematical and philosophical knowledge that in some ways still surpasses our own.

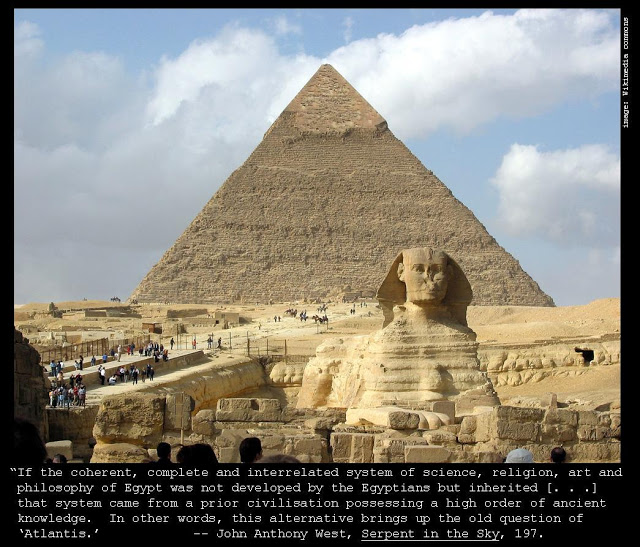

In his incredible 1976 text

Serpent in the Sky, John Anthony West explains the evidence that completely refuses to fit into the orthodox timelines of conventional anthropological orthodoxy:

Egyptologists postulate an indeterminate (and indeterminable) period of 'development' prior to the First Dynasty. This assumption is supported by no evidence; indeed the evidence, such as it is, appears to contradict the assumption. Egyptian civilisation, taken field by field and discipline by discipline (even according to an orthodox understanding of its achievement), renders unsatisfactory the assumption of a brief development period. The much vaunted flowering of Greece two thousand years later pales into insignificance in the face of a civilisation which, supposedly starting from a crude neolithic base, produced in a few centuries a complete system of hieroglyphs, the most sophisticated calendrical system ever developed, an effective mathematics, a refined medicine, a total mastery of the gamut of arts and crafts and the capacity to construct the largest and most accomplished stone buildings ever built by man. The cautiously expressed astonishment of modern Egyptologists hardly matches the real magnitude of the mystery. 196.

Further, Mr. West along with Robert Schoch have famously discussed the abundant evidence which argues that Egyptian civilization may have roots stretching much further back into antiquity than orthodox historians are willing to allow. Their discussion of the question of the

age of the Great Sphinx of Giza and some of its attendant megalithic temple complex indicates that it may be orders of magnitude older than even the First Dynasty (conventionally believed to have started around 3100 BC).

Mr. West's discussion of the misty antiquity before the First Dynasty is significant, and touches on many of the same difficult issues raised in the discussion of domestication presented above. He notes:

The archaeological record for the period preceding Dynastic Egypt is confused and incomplete. An number of neolithic cultures are thought to have existed, more or less simultaneously, from about 6000 BC onwards. These cultures built nothing permanent, apparently, and their arts and crafts were simple and rudimentary: there is no archaeological evidence that would support the notion of a prior great civilization -- with one possible exception.

These simple cultures had cultivated cereal grains and domesticated animals. The manner in which wild grains were originally cultivated and wild animals permanently domesticated is one of those questions that cannot be satisfactorily answered, but a period of long development is assumed. The fact is that throughout recorded history, no new animals have been domesticated; our domestic beasts have been around since the beginning, and no new grains have been cultivated.

The cultivation of grain and the domestication of animals probably represent -- after the invention of language -- the two most significant human achievements. We can fly to the moon today, but we cannot domesticate the zebra, or any other animal. We do not know how the original domestication was done, we can only guess. To attribute these immense achievements to people who could only chip flint and work crude mats and pottery is perhaps premature. It is plausible to suggest that, like the Sphinx and its temple complex, these inventions dated from an earlier and higher civilization. 228-9.

If Egypt was the recipient of some unknown and incredibly ancient and incredibly advanced civilization which existed long before 6000 BC, then the current human timeline of academic orthodoxy (and its unbroken centuries of mostly nomadic hunter-gatherer societies) is wrong.

If so, and if Egypt was the recipient of the ancient knowledge of that lost civilization, and if Egypt's priests preserved a tradition of abstaining from the eating of flesh (a tradition which descended from that ancient advanced civilization), then Plutarch -- who was after all recording what he had been taught by those Egyptian priensts -- may know something more than the peddlers of the modern evolutionary storyline (a storyline which may be correct but is certainly not the only storyline that fits the evidence, and in fact seems to have some serious trouble with some pretty extensive evidence that argues for a different timeline).

All this is not to suggest that those who follow the "Paleo Diet" and any other diet which rejects the twisted and damaging "

modern industrial diet" (which is really a product of the World War II and post-war era in industrialized nations, "led" by the "innovations" of the US in this regard) are not able to achieve health benefits due to the abandonment of the worst aspects of the typical US diet.

However, the advocates of that primarily meat-based diet should consider the possibility that their health improvements are less based on their consumption of meat and more due to the rejection of certain other modern dietary staples, and should consider the arguments that Plutarch makes against the shedding of blood in order to eat meat that comes from other sentient and conscious beings. They should also consider the possibility that the storyline of "paleolithic cavemen" pursuing a hunter-gatherer lifestyle for a couple million years before suddenly settling down and developing in fairly short order civilizations such as ancient Egypt might be seriously flawed, and that we should be careful before basing our entire lives on a historical model that may be nothing more than a modern evolutionary fiction.

In fact, based on the arguments above, it is at least possible that Plutarch is the one who was right, and that there existed an incredibly advanced ancient civilization which bequeathed to us domesticated grains for food, and domesticated animals for companionship and assistance in farming, gifts which could not have been developed in the manner that evolutionary professors since the end of the 1800s have been teaching that they were developed. If the testimony of the priests of Egypt is correct, then this ancient civilization taught at least some form of vegetarianism, and the subsequent lapses into more primitive hunter-gathering and other forms of meat-eating were a devolution from the original plan.

Thus we see that Plutarch's two essays "

On the eating of flesh" are incredibly important, important even beyond the very important question of what kind of diet is best for mankind. For they open a fascinating window onto the question of mankind's ancient past, and where the grains we eat and the domestic animals we take for granted came from in the first place.